World Energy Outlook 2025 takes a step back by eliminating the Announced Policies Scenario (APS)

The International Energy Agency has always built its authority on policy. Its World Energy Outlook models are maps of intent: what governments say they will do, not necessarily what markets or industries are already doing. That worked when energy transitions moved at a bureaucrat’s pace. But today, the engine of change is industrial, not political. China — through sheer manufacturing scale and global electrification reach — is driving a transformation that the IEA’s scenarios struggle to capture.

The agency dropped APS from the World Energy Outlook 2025, saying that national commitments are too uneven to model reliably. Instead, it focused on the Current Policies and Stated Policies Scenarios. In effect, the IEA narrowed its gaze to a future far more friendly to oil and gas. A world that changes, but only as fast as formal policy permits. Yet the real world is moving faster, driven not by pledges but by production lines and industrial policy.

China: The Electrifier-in-Chief

Over the past decade, China has fused state planning, industrial finance, and scale to build the world’s most powerful clean-energy ecosystem. In 2024 alone, it sold 12.8 million New Energy Vehicles and exported 1.3 million more. It now accounts for roughly 60 percent of all new renewable capacity installed globally each year. Its solar panel manufacturing capacity will soon exceed the United States’ total electricity demand.

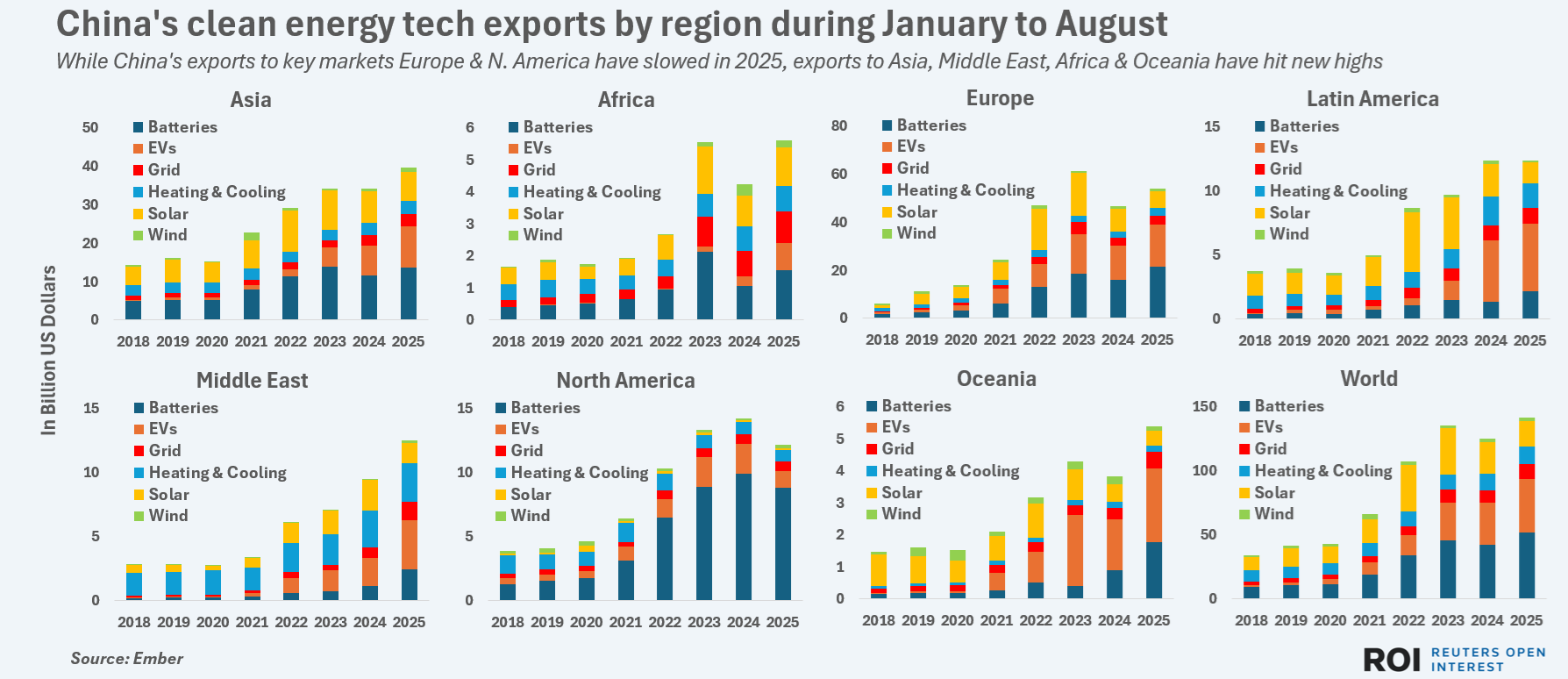

This is not just an energy story; it is an industrial one. Chinese automakers — BYD, SAIC, Geely, Changan — are flooding the Global South with affordable sub-$20,000 EVs, the ubiquitous two- and three-wheelers, bundled with charging networks, battery-recycling plants, and joint-venture factories. Beijing’s “industrial diplomacy” is electrifying emerging markets in the way Western aid once sought to wire them for fossil fuels.

The IEA sees policy diffusion as the main driver of energy transitions. China shows us something else: industrial diffusion. What the IEA calls “infrastructure limitation” in Africa, Southeast Asia, and Latin America is being dismantled by Chinese capital, logistics, and engineering. Electrification is becoming an export commodity.

The Physics of Scale

The story that the IEA’s model misses is not ideological; it’s arithmetic. Every doubling of cumulative solar production cuts costs by about twenty percent; every doubling of battery output by roughly eighteen percent. Those learning curves compound faster than politics can keep up. In 2010, a battery pack cost over $1,000 USD per kilowatt-hour; by 2023, $130. By 2030, it may hit $60. Solar module prices have fallen by over ninety percent since 2010.

Once parity arrives, substitution accelerates. Each ten million EVs on the road displaces around half a million barrels of oil demand daily. At projected adoption rates, that’s the equivalent of erasing an entire Saudi Arabia of oil demand within a decade.

This is the industrial feedback loop that OPEC, ExxonMobil, and the U.S. Energy Information Administration have consistently failed to model. Their scenarios assume hydrocarbons’ dominance and treat innovation as exogenous, a polite way of saying “someone else’s problem.” The IEA broke from that orthodoxy with the APS, which embedded learning curves and cost feedback. Yet by retreating from APS in 2025, the agency risks losing sight of the very dynamics that once made it the gold standard.

The Global South’s Leapfrog

Look beyond Beijing. Across the Global South, Chinese-financed solar farms, grid-stabilization projects, and electric-mobility programs are rewriting development logic. In Kenya, rooftop solar is offsetting diesel generation. In Brazil and Indonesia, low-cost Chinese EVs are scaling faster than policy incentives can track. In the Middle East, Chinese firms are co-building battery-storage complexes once thought decades away.

This diffusion matters because it shifts the geometry of the transition. For decades, energy modernization flowed North to South. Today, it runs in reverse. China’s overcapacity — derided in Western policy circles — is accelerating global deployment by forcing prices down. The IEA’s models, calibrated to declared policies rather than industrial momentum, under-represent this structural feedback.

Capital Flows Tell the Truth

Follow the money. Global clean-energy investment surpassed $2 trillion USD in 2024 and continues rising about 6–7 percent annually. Fossil-fuel investment, meanwhile, has plateaued or declined. Capital allocation now looks more like APS than like the new CPS (Current Policies Scenario), or even the still conservative Stated Policies Scenarios (STEPS). Markets are already betting that electrification, not hydrocarbons, defines the mid-century energy mix.

If the IEA’s CPS and STEPS project fossil demand growth into the 2040s, they describe a world that capital markets have already abandoned. APS aligns more closely with where investors are placing real money — grids, storage, batteries, renewables, and electrified transport.

The Model and the Machine

What’s unfolding is a divergence between two kinds of forecasting: the model built on policy, and the machine built on production. The model counts regulations; the machine multiplies learning. The IEA’s WEO 2025 treats electrification as an outcome of government intent. But China’s industrial ecosystem shows it is increasingly a self-propelling system — feedback, not fiat.

This is not to diminish policy. Without it, China’s ecosystem would not exist. But policy there functions as scaffolding for industry, not a ceiling. The IEA’s omission of APS makes sense within its institutional DNA; it reflects what can be officially promised. Yet it leaves unmodelled the real-world force now shaping the transition: manufacturing momentum.

The Consequences for Analysts and Policymakers

For analysts, the lesson is simple: the energy transition is being built, not legislated. The baseline for understanding it is no longer the pace of policy but the speed of industrial learning. For policymakers, particularly in countries like Canada still investing billions in hydrocarbon expansion, the implication is brutal. The world is electrifying faster than you can permit a pipeline.

The APS still fits the facts because it embeds the physics of feedback. The IEA may have stopped publishing it, but China is still proving it — one gigafactory, one grid, one EV fleet at a time.

Be the first to comment