This article was published by the International Energy Agency on Nov. 6, 2025.

By Brian Motherway, Head of Energy Efficiency and Inclusive Transitions Office

Efficiency is more relevant now than ever

Governments around the world place high priority on ensuring that energy is accessible, secure, affordable and sustainable. A crucial part of meeting this challenge is improving energy efficiency, which remains one of the fastest and most cost-effective ways to strengthen energy security, lower costs and reduce emissions.

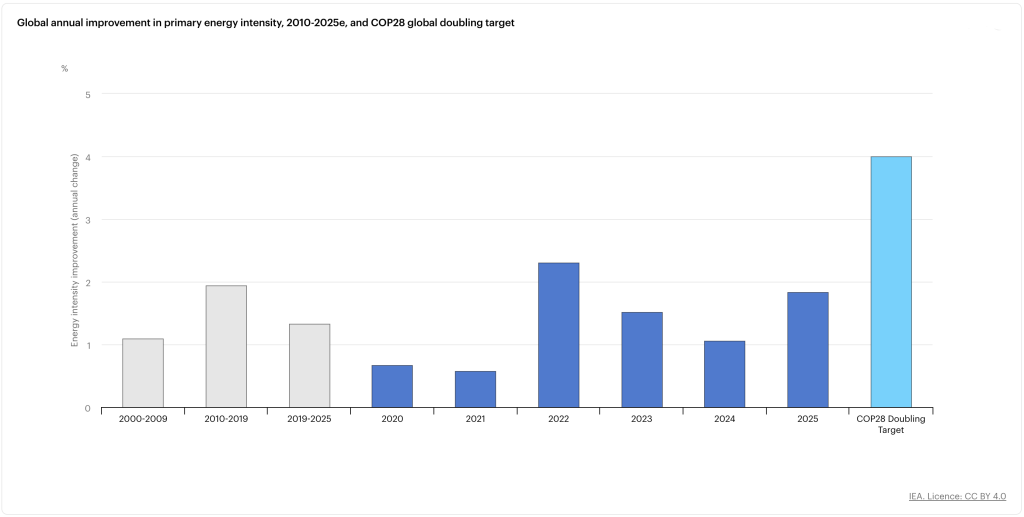

Two years ago, at COP28 in Dubai, nearly 200 governments recognized the central role of efficiency, agreeing on the goal of doubling the average annual rate of global energy efficiency improvements to 4 per cent per year by 2030.

At the time, IEA analysis had shown that this goal was achievable. Over the first 20 years of this century, energy efficiency improvements, as measured by the rate of change in primary energy intensity, had followed a steady trend, accelerating from an average of around 1 per cent per year from 2000 to 2009 to about 2 per cent per year from 2010 to 2019. We showed that the technologies and policies already existed to double that rate of progress – with 9 in 10 countries achieving a rate of 4 per cent or more at least one year in the past decade.

However, as leaders gather in Belem, Brazil, for COP30, we must take stock and recognize that global progress on efficiency is still not where it needs to be.

The world remains off track for the goal of doubling efficiency progress

The latest data from the IEA show that, in recent years, rather than increasing towards the 4 per cent goal, global efficiency progress has slowed. The average annual improvement since 2019 is only 1.3 per cent, well below the starting point for the doubling goal. We expect to see that rise to about 1.8 per cent this year, which is a small step in the right direction, but the world is still well off track to meeting the 2030 goal.

Four key trends help explain why we are stuck in low gear

Global energy intensity progress is shaped by a wide range of factors, but four key trends help explain why current efficiency progress is slow.

Around two-thirds of global final energy demand growth since 2019 has been concentrated in industry, a sector where energy intensity progress has slowed sharply. Industrial energy demand growth has accelerated since 2019, while the average annual rate of industrial energy intensity improvement fell to under 0.5 per cent over that same period, compared with almost 2 per cent last decade. This global shift towards more intensive energy use in industry is offsetting gains made in other sectors and is a drag on overall efficiency progress.

Policies have lagged technology progress, leaving significant savings on the table. Many efficiency policies have not been updated to match recent technological gains. Today, many appliances are often only half as efficient as the best models, showing how policy has fallen behind technology. For example, the efficiency of best-in-class lightbulbs doubled in the last 15 years, while minimum performance standards have only gone up by 30 per cent. If policy does not keep up, consumers waste money and an opportunity to reduce emissions is missed.

Increased access to air conditioners has pushed up cooling-related electricity demand. Higher living standards have allowed more people to afford much-needed cooling technologies such as air conditioners, especially in emerging economies. In fact, energy to keep people cool has seen the fastest growth of any end-use in buildings this century. But people are not always enabled or encouraged to buy the most efficient air-conditioning units, which means using them costs more than it needs to. If every air conditioner bought since 2019 had been the most efficient available, as opposed to the typical lower efficiency models that were bought, the world could have avoided electricity demand growth equivalent to the demand growth of data centres across the globe over the same period.

Accelerating electricity demand growth has, in some regions, led to an overall increase in less efficient power generation. In many regions, rising electricity demand is being met by more efficient technologies such as renewables. However, in some key regions, rapid demand growth is leading to greater use of older, less efficient generation sources, placing upward pressure on primary energy demand and slowing energy intensity progress. This highlights how the COP28 goals of doubling efficiency progress and tripling renewables capacity complement each other.

There are some glimmers of hope in our new 2025 data. Policy making is certainly accelerating in many areas, and preliminary estimates for 2025 show some strong progress in key regions. India, for example, is set to see intensity progress accelerate to more than 4 per cent this year. But without further action, longer-term trends still suggest global progress will remain well below the doubling target agreed at COP28.

Governments have the opportunity to raise ambition and close policy gaps

There are many good examples of effective energy efficiency policies across the world, and new ones are being introduced regularly. In fact, countries representing 85 per cent of global energy demand announced between them over 250 new or updated policies in 2025 alone. This forms the basis for faster progress, particularly in two critical areas:

First, governments can move quickly to raise the ambition of existing policies. Technology is improving, and policies need to be kept up to date. In some countries, for instance, a building that meets the local efficiency standard may in fact be using three times as much energy as one in another country with a similar climate but with higher efficiency standards. There is significant room to raise the bar and accelerate progress using existing and well-proven policy tools. When policy frameworks are already in place, this represents the fastest and easiest way to accelerate efficiency progress.

Second, important policy gaps remain. There are still many areas where policies are absent. For example, around half of countries globally still do not have efficiency standards for new buildings, including in regions experiencing rapid growth. Governments can prioritize and focus on technologies and sectors with the highest energy consumption or the greatest potential for improvement.

The potential payoff is enormous and extends well beyond energy

Doubling energy efficiency progress means taking action to improve people’s lives. Energy efficiency delivers multiple benefits to people, companies and countries. Without efficiency gains since 2010, today’s greenhouse gas emissions would be 20 per cent higher, and efficiency actions over the past two decades have lowered consumer bills, improved industrial competitiveness and enhanced energy security.

Countries around the world are recognizing this. Earlier this year, nearly 50 governments endorsed efficiency as a key tool to enhance energy affordability, quality of life and industrial competitiveness at the IEA’s 10th Annual Global Conference on Energy Efficiency.

The IEA will continue to work closely with governments seeking to improve energy efficiency. We have mapped the best policies from around the world in our Energy Efficiency Policy Toolkit, and on 20 November, we will launch the Energy Efficiency 2025 report, where these and other key trends will be analyzed in more detail.

Be the first to comment