CEPA (Canadian Energy Pipelines Association) consistently emphasized that the NEB (National Energy Board) was the best placed regulator to oversee the full cycle of a pipeline from beginning to end…If the goal is to curtail oil and gas production and to have no more pipelines built, this legislation may have hit the mark. – Chris Bloomer, CEPA CEO appearing before the Standing Committee on the Environment and Sustainable Development of the House of Commons reviewing Bill C69, March 29, 2018.

If Chris Bloomer is correct, Bill C69 is a major blow to the energy industry, forecast to grow production by another 1.7 million b/d by 2038 – crude oil that will require another pipeline or two by then – and already struggling to ship product to market. Why would Justin Trudeau and the Liberals deliberately hamstring Canada’s biggest exporter?

Do they hate oil and gas (a common refrain in Alberta)? Dennis McConaghy is convinced they do. The former VP for TransCanada Pipelines, who oversaw the contentious Keystone XL project, is apoplectic about C69.

“C69 is the revenge by Katherine McKenna (Canadian environment minister), with the support of Gerry Butts (principal secretary to the Prime Minister) and Zoe Caron (chief of staff to the natural resources minister), the quid pro quo for abiding the Trans Mountain Expansion approval. This is the poison pill to ensure that future hydrocarbon development is not happening in this country,” he told Energi News.

Strip McConaghy’s comments of their anger and frustration, and he has a point.

Butts is the former head of World Wildlife Fund Canada and and no fan of building more pipelines prior to taking up the top job at the Prime Minister’s Office after the late 2015 federal election. Caron co-authored the book Global Warming for Dummies with Green Party leader Elizabeth May, worked under Butts at the WWF and then at the PMO, and is a prominent advocate for climate policy and renewable energy. She succeeded oil and gas executive Janet Annesley in the natural resource minister’s office in May, 2017 about the time the NEB modernization panel reported and the process that led to C69 kicked into high gear with the release of the federal government’s discussion paper in late June. She retained her position even after Amerjeet Sohi succeeded Jim Carr as minister in 2018, a fact not lost on critics like McConaghy.

The problem with McConaghy’s conspiracy hypothesis is that expert sources interviewed by Energi News don’t buy it.

“There’s speculation there about intent for which we have close to zero evidence. We’re talking about circumstantial interpretation. I have not the faintest clue and I don’t think they do either. Well, that’s not entirely true. There’s probably a faint clue but they’re reading a whole lot of things from a particular perspective and they’re probably not seeing a broad enough view,” Robert Gibson, a professor with the School of Environment, Resources and Sustainability at the University of Waterloo, and an expert on environmental assessment law and process, told Energi News.

Gibson cautions that the federal government review and consultation process, which began in early 2016, should not be discounted as the prime mover of the changes enshrined in the new legislation. He points out that Environment Minister Catherine McKenna’s advisory committee on environmental assessment has 20-odd members, including six members each from industry, indigenous communities, and environmental groups, with a few from provincial governments thrown in for good measure. CEPA occupied one seat at that table. And a lone voice is easily drowned out by the others – or ignored, if you favour McConaghy’s point of view.

When it comes to working the process, Gibson thinks other groups were more sophisticated and influential than pipeline representatives.

“My impression, having been at the table at many of these things, is that speaking very broadly the mining people know more. They’ve had more experience in assessments, they are much more veteran, know what the fine print means, and have probably a deeper direct connection to understanding the importance of the Constitutional foundation of the indigenous perspective and the indigenous rights component of putting together assessment law, none of which seems to have gone on with the people who claim to be proponents of the oil patch,” he said.

Bloomer and other industry-friendly critics of C69, such as Martha Hall Findlay of the Canada West Foundation, dispute this view. They argue that oil and gas representatives were actively engaged throughout the process.

“We were, for roughly two years, engaged in problem-solving, providing input and constructive comments, into the process that ultimately brought C69 forward. We felt that all that work and effort did not really amount to an awful lot in terms of what came out of the original bill,” he said.

Bloomer isn’t the only industry player who felt ignored. After the the first draft of C69 was released, Findlay’s organization prepared a detailed critique entitled Unstuck that fell on deaf ears, she said: “We appeared before the House of Commons committee, as did a number of organizations, outlining those concerns and were really disappointed, frankly, that virtually none of the recommended amendments were taken into consideration or supported by the House.”

What’s going on?

Simply put, the main responsibilities of the NEB are provided in the NEB Act and include the regulation of the construction and operation of interprovincial and international oil and natural gas pipelines, international power lines and designated interprovincial power lines. For the pipelines under its jurisdiction, the NEB also regulates tolls and tariffs. In addition, the NEB regulates the export of natural gas, oil, natural gas liquids, and electricity, and the import of natural gas. – NEB Modernization Panel Report, P. 17.

The Stephen Harper Conservatives revised the Canadian Environmental Assessment Act in 2012 and gave the oil/gas/pipeline industry pretty much everything it wanted, particularly the need for intervenors to have “standing” – that is, to be directly affected by a project before being allowed to participate. Industry was pleased with those changes, views the NEB as a respected world-class regulator, and is adamant that only modest reform to improve both regulation and project assessment is required.

“CEAA (Canadian Environmental Assessment Act) 2012 was part of the omnibus budget bills of 2012 (C-38). Industry got to pretty much pick and choose what it wanted. So its fair to say CEAA 2012 reflects what in their view is the appropriate bargain between encouraging development and environmental protection, and they take umbrage at any tweaking,” Martin Olszynski, assistant law professor at the University of Calgary, said in an interview.

Justin Trudeau, on the other hand, sided with Canadian environmental and indigenous groups opposed to Enbridge’s Northern Gateway and Kinder Morgan’s Trans Mountain Expansion projects, who argued that the regulator was captured and that its assessments were a sham.

The 2015 Liberal platform promised to “immediately review Canada’s environmental assessment processes and introduce new, fair processes” that restore robust oversight and thorough environmental assessments and “respect the rights of those most affected, such as Indigenous communities.” It also included a phrase that came back to haunt Trudeau after the election: “While governments grant permits for resource development, only communities can grant permission.”

This is the fundamental conflict between industry and the Trudeau Government. Once the Liberals committed to “modernizing” Canadian energy regulation and project assessment, industry was never going to be happy with the final outcome.

Industry complaints fall into two broad categories.

One, leave the NEB alone.

Bill C69 creates the Canadian Energy Regulator, but the new agency appears to have all of the old regulatory functions of the NEB. Pipeline reviews will be conducted by another new body, the Canadian Environmental Assessment Agency, whose employees will take years to get up to speed for linear infrastructure projects, according to Kenny: “I was an executive at the NEB when the CEAA was initially introduced in the early 90s. It was difficult to get to a place of pragmatism, it took about a decade.”

The national energy regulator has decades of expertise that cannot easily be transferred to the new Agency, she says. And no pipeline operator will test the new processes, rules, and the agency established by C69 because an environmental impact assessment can easily cost $1 billion or more.

Investors were more – though increasingly less – confident in the old system and as much of it as possible should be retained.

Two, too many of the new rules in C69 are undefined and vague.

Defenders of C69 – and there are many in the academic and environmental communities – say that uncertainties can be resolved in the regulations and during implementation.

For the mining sector, agency and ministerial discretion is actually an advantage, says Pierre Gratton, CEO of the Canadian Mining Association.

“No mine is the same. It’s in a different location, it’s a different commodity, there are different communities. The issues vary. You can’t have a one-size-fits-all approach,” he said in an interview. “You can’t be prescriptive in mining, otherwise you open the door to litigation. The government uses discretion in part to protect itself from litigation and that’s where I sort of don’t quite understand why some, like Martha Hall Findlay, think that more prescription is good.”

Brenda Kenny, former head of CEPA, a member of the NEB modernization panel, and now an independent consulting engineer, says the pipeline industry has a different view of discretion: “The issue is how much money do you put at risk? How long are you prepared to carry at-risk capital? How long can you endure uncertainty? Will the project hit a particular market window before it closes? At-risk capital and time certainty are fundamental to pipeline project planning and at this point proponents don’t feel confident that either of those are really secure in Bill C69.”

Industry simply doesn’t trust the federal government to get it right, as the comments by Bloomer, Hall Findlay, and McConaghy demonstrate.

But if pipeline companies want Ottawa to backtrack on C69 and modernize the NEB instead, they have to somehow convince politicians the NEB was never broken to start with.

Is the NEB broken?

We are now in the midst of assessing permanent reforms to environmental assessment in Canada. That’s not just the National Energy Board. That would include the Canadian Environmental Assessment Agency and also a review of a number of acts of Parliament. [The review is] designed to restore public confidence in the process. The goal is to ask all of the right questions, put everything on the table, and emerge with a set of processes that reflect the realities of 2016, that respect the importance of partnerships and meaningful consultations with indigenous communities that understand we have international and domestic obligations to limit greenhouse gas emissions. Our strategy is to create a process, and room for all Canadians who have an interest in major projects, to express themselves. – former natural resources minister Jim Carr, June 2016 interview with Energi News

Environmental groups’ criticisms of the NEB are summed up in this comment from the submission by the Environmental Defence Council to the NEB modernization panel:

Public confidence in NEB regulation, project reviews, and decision-making has plummeted, resulting in a situation that is not working for stakeholders, whether they be industry proponents, opponents of a project, the federal government, First Nations, or the Canadian public. The problems with the NEB, and energy regulation and natural resource management in Canada more broadly, run deep and cannot be addressed by modest reforms and tinkering around the edges. EDC urges the Expert Panel to recognize the need for a substantial overhaul of energy and environmental regulation and build a new regulatory regime that protects Canada’s environment and natural capital, aligns energy regulation with Canada’s climate commitments, and fulfills the federal government’s promise to balance a healthy economy with a healthy environment.

Gaetan Caron, NEB chair from 2007 to 2014 under the Conservatives, is having none of it.

“If you looked at the last five years, all the criticism directed at the NEB process is not specific to any error the board made in its judgement or in its procedural choices,” Caron told Energi News in a 2016 interview. “I’m unable to find a flaw, a mistake, an error that the NEB made in dealing with the Northern Gateway and Trans Mountain Expansion projects. Name me a flaw that requires attention to fix the NEB. My list is empty.”

In fact, industry argues that pipeline opponents deliberately attacked the NEB review processes, doing their best to render them inoperative, exploiting vulnerabilities in those processes whenever they could, as part of their strategy to kill both Northern Gateway and Trans Mountain Expansion.

“You had all sorts of indigenous people wanting to be heard at the NEB. You had all sorts of environmental activist groups wanting to be heard at the NEB. The NEB was never set up to have that kind of number of people showing up, but there was no other place for those concerns to be heard,” says Hall Findlay.

This is a key point for industry: Canada does not have a national energy strategy. There is a process of sorts underway being run by the Generation Energy Council that released a report in June, but that’s not a strategy drafted by the Canadian government and approved by Parliament, say critics, who argue that strategy should come before policy.

“I was very clear that Canada needs to clear up the policy issues and the political issues before a pipeline project goes through the environmental impact assessment process. That has to be dealt with up front,” said Bloomer.

Does Canada want to be in the hydrocarbon business? Is oil and gas investment, and the jobs and business activity it creates, more important than meeting national and provincial climate targets? Should we put more resources into clean energy and developing cleantech technologies rather than a sunset industry whose assets could be stranded if the energy transition happens sooner than expected? If Canada is really committed to the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, as the Trudeau Government claims, then what role do First Nations and other indigenous communities want to play in resource development?

“Inherently, in a NEB hearing today, you get a policy debate rather than a project debate,” says Kenny.

But the national regulator is not structured to accommodate policy debate, says Caron. It is very strictly limited to what it can and cannot do by the NEB Act, first passed in 1959, and he says that under his leadership pipeline assessments adhered strictly to the letter of the legislation.

Is it any wonder then that the NEB came to be viewed as a “captured regulator”?

Is the NEB a “captured regulator”?

We heard that Canadians have serious concerns that the NEB has been ‘captured’ by the oil and gas industry, with many Board members who come from the industry that the NEB regulates, and who – at the very least appear to – have an innate bias toward that industry. Canadians told us that, while energy industry expertise is critical, they expect to see NEB Board members who represent a broader cross-section of Canada, and wider scope of knowledge and experience, particularly Indigenous knowledge, regional understanding, and climate science. – NEB Modernization Panel Report, P. 7.

McConaghy, who as a pipeline executive is intimately familiar with the NEB, argues that the allegation that the NEB is a captured regulator has never been proved by any objective evidence.

“The NEB has been vilified for having recommended the approvals of TMX and Northern Gateway, but for no reason other than the NEB did not accept the ENGO (environmental non-government organization) position that any incremental oil sands production must be resisted, thereby frustrating its growth by denying additional pipeline capacity. Of course, it is not the role of the NEB to make that judgement, but rather via the political process,” he said in an email.

“What the ENGOs resent is that competent, professional and unbiased regulators consistently validate the fundamental value and environmental acceptability of these projects.”

But Prof. Meinhard Doelle, Schulich School of Law at the University of Dalhousie, says the NEB is a captured regulator in the sense that if you put it in charge of a broader assessment process, it will tend to view the industry it regulates favourably, and will be inclined to overvalue its contribution and undervalue other impacts, benefits, risks and uncertainties.

“For environmental assessment purposes, it is a captured regulator in the sense that it is not the best institution to gather information about the broader implications of a proposed oil and gas project, and certainly not the best institution to decide whether or under what conditions the project should be approved. That is not to say it is not a suitable regulator of projects that are approved,” he wrote by email.

Robert Gibson, a professor in the School of Environment, Resources and Sustainability at the University of Waterloo, thinks the issue isn’t quite that black and white because there is no formally defined line between “friendly” and “captured.”

“Certainly it is safe to say that the Board as regulator and the hydrocarbon, pipeline and other subject industry regulatees have been close for decades, probably since the Board was established in the 1950s,” he said in an email.

“Such closeness, and the consequent inclination to see eye-to-eye, is a common phenomenon where regulators and regulatees share fairly specialized expertise, spend a great deal of time together, have employees who often went to university together, and frequently exchange staff, etc.”

There is considerable research on regulator capture in pollution control and finance, he says, and the problem is most evident where the regulator is also an advocate for the industry: “The case of the NEB is a little more complex because under the Harper government the NEB served a prime minister and cabinet that were vocal advocates of pipelines and other projects while the NEB was reviewing them.”

Bloomer strongly disagrees with Doelle’s view of the regulator and says that it’s a “big point” for industry, perhaps the most significant objection to Bill C69. He says CEPA supports modernizing the NEB, such as changes in governance that would broaden diversity among board and review panel members. But industry is adamantly opposed to removing the assessment function from the regulator.

“We said this right from the get-go, we don’t think the NEB was broken. The NEB has been a very competent regulator for a very long time. We don’t need to burn down the house and rebuild it,” he said. “That was very destructive to approach it that way, when really valid changes could have been made and should have been made. We got lost in this whole thing about the NEB being broken.”

Is there really a public “crisis of confidence” in the NEB?

“In our consultations we heard of a National Energy Board that has fundamentally lost the confidence of many Canadians,” the modernization panel wrote in its report.

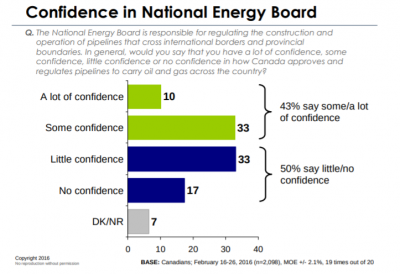

An EKOS poll that surveyed several thousand respondents in 2016 found that fully half of Canadians have little or no confidence in the NEB, versus 43 per cent who have some or a lot of confidence.

An EKOS poll that surveyed several thousand respondents in 2016 found that fully half of Canadians have little or no confidence in the NEB, versus 43 per cent who have some or a lot of confidence.

But there is another side to this debate: that nine of out of 10 Canadians don’t know enough about the regulator to hold an informed opinion one way or the other, according to an Environics survey from the fall of 2017.

“Industry advocates think the NEB process is fine, opponents think it deeply flawed and the majority of Canadians know little of the Board or its processes. The evidence suggests a generalized lack of awareness of what the NEB is and does, rather than a widespread crisis of confidence,” writes Tony Coulson, group VP of corporate and public affairs, who concludes that “a minority was successful in putting forward a narrative – that of a crisis of confidence – that may not have reflected public opinion.”

In the end, much of the angst felt by industry and its supporters, like Hall Findlay, comes from the belief that the NEB needed only minor tinkering instead of a major overhaul. The environmental assessment system was familiar and efficient, from their point of view. Because the Trudeau Liberals bought into the environmentalists’ criticisms of the NEB as broken and captured, any changes to that system were inevitably viewed as suspect.

Their calls for greater certainty can be seen as a response to the greater uncertainty created by a new system that has not been tested and found satisfactory.

“It’s important that people understand we actually wholeheartedly support the intentions of the bill. To the extent that the government is hoping to figure out a way for Canada to harness our resources in an environmentally sustainable way, we’re all over that. We think that’s extremely important, wholeheartedly support it. Our issue is just that we don’t believe that bill C69 does this and, in fact, likely would create even more uncertainty and do even more harm to our currently already bad investment climate,” Hall Findlay said.

So, what does C69 do and not do?

Is C69 a logical evolution from CEAA 2012?

CEAA 2012 fundamentally altered the federal environmental assessment regime from one that assessed the effects of federal decision-making broadly to one that focuses almost exclusively on large resource projects…All of these changes did not, of course, go unnoticed. They were met with considerable opposition by Indigenous peoples, environmental groups, scientists, and former politicians – both liberal and conservative. Ultimately, ‘restoring lost protections’ became a key plank of the federal Liberal campaign in 2015. – Martin Olszyinski, Bill C-69’s Detractors Can Blame Harper’s 2012 Omnibus Overreach, Sept. 25 2018 Ablawg post.

According to Olszyinski, the original Canadian Environmental Assessment Act regime from 1992 applied whenever the federal government was the proponent or financed the project, federal lands were involved, or it issued a permit or authorization. This last function was the most common, with thousands of assessments being conducted each year.

Big changes arrived in 2012 when the Harper Government, responding to pressure from the oil and gas industry, scrapped the original legislation and passed CEAA 2012. Significant modifications included limiting participation during the review to people “directly affected” by the development (generally, those owning property within one kilometre from the project), lowered the number of assessments to 60 or 70 major projects per year, reduced protection of fish habitat and water bodies, and gave Cabinet rather then the NEB final authority to approve or reject pipeline projects.

From Olszyinski’s point of view, Bill C69 “is best characterized as a CEAA 2012-plus regime,” retaining the focus on major projects, still allowing proponents to drive project assessments, and it “does not draw an environmental – or any other – line in the sand. It merely requires the government to identify and consider impacts in a transparent manner.”

Though he mostly agrees with Olszyinski, Doelle has a slightly different perspective. He sees Bill C69 as a logical progression from the original 1992 Act, which allowed any federal agency or department to undertake an environmental impact assessment for projects that fell within its purview. The Conservatives changes in 2012 for the first time handed that responsibility to a single agency, with two exceptions: the Canada Nuclear Safety Commission and the NEB. The new Impact Assessment Act that is part of Bill C69 does away with those exemptions.

“One way to look at what the Liberals have done is they continued what the Conservatives started, which is to take the assessment out of the hands of the regulators or the decision-makers and put it in the hands of an independent agency. Having said that, the independent agency still doesn’t make decisions. What they do is carry the process. They are in charge of the process, and then the ultimate decision is either made by a minister or cabinet,” he said in an interview.

The pros and cons of C69

The legislation is an omnibus bill that includes separate acts on impact assessment, energy regulation, and navigable waters. Third reading in the House of Commons occurred on June 20 after an unusual number of “key amendments.”

“If a bill has to have more than 150 amendments come from the government itself, doesn’t that tell you maybe it was a bit of a scramble?” said Linda Duncan, an NDP MP and vice-chair of the House environment committee.

“Few are happy with the result, including scientists who say the bill puts too little emphasis on the scientific rigour and independence of impact assessments,” science reporter Ivan Semeniuk noted in the Global and Mail. “Opposition members expressed surprise that the government hasn’t done better after two years of public consultation and expert panel recommendations.”

All signs point to Bill C69 passing the Senate relatively unscathed, but the changes passed in the House have done little to silence the legislation’s critics.

“We applaud the government’s intentions. We absolutely need to harness our resources in an environmentally sustainable way – and we can. Unfortunately, despite these good intentions, the bill would create more problems than it hopes to solve,” the Canada West Foundation wrote in late Sept.

“Bill C-69 is absolutely the wrong thing to do right now, because it will set our entire project-approval process back to square one, and reopen every potential economic development project to a new round of protests, court battles, years of delays and investment uncertainty.”

But C69 also has defenders, including most of the mining sector, environmental groups, and many academics and analysts who specialize in environmental impact assessment.

1. Single agency concept – end of assessment by regulators

Bill C-69 carves out the review of major pipeline projects and places it with the new Impact Assessment Agency…That new Agency does not have the rich history of administrative decision-making and technical expertise of the NEB. Instead, the new Agency is mandated to perform a broadened role, assess a wider scope of issues and is expected to implement the government’s political agenda related to climate change, reconciliation and gender objectives. It is not an independent, expert regulator. CEPA is not convinced that it will have the capacity to conduct these broadened, political reviews, even with the announcement of $1 billion of new spending to support the implementation of the Impact Assessment Act. – CEPA submission to Parliament.

Chris Bloomer and CEPA didn’t pull any punches – that sentiment is widely shared in Alberta and almost universal within the energy sector, as we saw earlier with the comments from Dennis McConaghy and others. Removing assessment from the energy regulator is simply a bridge too far for industry.

“For pipelines, it’s also a concern just how responsibilities will transfer to the CER from the NEB – and what the hiving off of environmental impact assessment means for the integrated assessment for which the NEB has been responsible,” says Bishop. “There’s fear that NEB processes and expertise will be lost.”

But Nichole Dusyk of the Pembina Institute points to the Federal Court of Appeals overturning of the Trans Mountain Expansion in part because of a “critical error” on the part of the NEB as evidence that impact assessments must be conducted by professionals with expertise and experience or costly mistakes will be made.

“The National Energy Board made an error in how it interpreted the Canadian Environmental Assessment Act,” she said in an interview. “All industries should have the same lead agency conducting environmental assessments so consistency and similar standards are applied to all projects.”

But the Canadian Energy Regulator will still exert influence because it will sit on pipeline review panels and provide expertise and input to the assessment process. Bob Gibson argues the regulator’s involvement will dilute the independence Dusyk sees as the principal benefit of the new agency.

“The actual shift in the IAAct in C69 is incomplete, given the influential roles retained by the NEB and CNSC [Canadian Nuclear Safety Commission] and the strengthened roles of the offshore [oil and gas regulatory] boards,” says Gibson.

Nor does C69 exclude the sticky fingers of other federal departments. While the CER will not assess new pipeline projects, “that is essentially where the guiding principle ends,” according to the Canadian Bar Association:

Many projects to which the Act applies, such as pipelines, would require assessment under other Acts, such as the Fisheries Act. In those cases, the one project – one assessment guiding principle would not be met. Subjecting projects to multiple assessments raises the potential for multiple regulatory and judicial challenges to approval or authorization of a single project.

2. Early planning/engagement phase/national interest

“A key concern with the current process is that despite all of the rules and process having been complied with, and despite the regulator’s recommendation for approval, a small group of politicians (the federal cabinet) was able to pick and choose which project(s) they would, in the end, approve,” the Canada West Foundation said in a submission to Parliament.

Canada West is referring to the Trudeau government’s decision in late 2016 to approve Trans Mountain Expansion but to revoke cabinet approval for Northern Gateway, in part because the former was “in the public interest” and the latter was not.

What does it mean for a pipeline to be in the public interest? For the first time, Bill C69 defines it as the project’s contribution to sustainability, adverse effects within federal jurisdiction, impact on indigenous rights, and contribution to meeting or not meeting Canada’s greenhouse gas emissions reduction targets.

The legislation provides a 180-day period during which affected and some interested parties in the project can comment on the proposed project. More focus on consultation before the formal – and costly – part of the assessment gets under way.

“This formalizes an assessment step already taken by many veteran proponents through consultations with associated jurisdictions and important interests,” said Gibson. “It adds more transparency, and potentially greater credibility than a step led by proponents with particular interests.

Pre-planning has both detractors and defenders.

“The level of detail and time required to determine public interest is a concern. The two-phase approach that many proposed would confirm major policy ‘go/no go’ decisions in less than a year. As proposed there is still a high risk that over a billion dollars may be spent before any clear indication that the project is viable,” said Kenny.

The environmental impact assessment expert panel recommended taking project assessments largely out of the hands of proponents. The government refused to do that. This is a gesture in the direction of the most impartiality.”

A brief from the Canadian Bar Association worries about the “potentially limitless discretion” to extend deadlines for pipeline pre-planning.

“The addition of a 180 day (or more) planning phase determination on whether an impact assessment is required for a designated project, while requiring broad public, Indigenous consultation and engagement with jurisdictions risks adding significant time and cost to the process,” it says.

The new approach should lead to “efficiencies” from early clarification of requirements and expectations, says Gibson: “Effectiveness depends on the willingness and capabilities of all participants, including proponents and stakeholders, as well as the relevant authorities. But it could also suffer from bureaucratization.”

3. Uncertainty, lack of clarity and ministerial discretion

Ministerial and federal cabinet discretion is a longstanding contributor to uncertainty, according to Gibson.

“Discretion under the IAAct is constrained somewhat by explicit requirements for factors to consider and mandatory public reasons for decisions, but is still pervasive,” he said. “Examples include determination of the categories of projects to which assessment requirements will be applied, and decisions on what strategic and regional assessment will be undertaken, with what mandates and what anticipated products.”

Alberta Premier Rachel Notley says her government agrees with the high-level objectives of Bill C69, but likens the legislation to putting “two lawyers in a room and you’re going to get six opinions.”

While she acknowledges the Trudeau Government’s intention to create a regulatory regime that is trusted by everyone, and blames the Harper government for polarizing the national debate over energy infrastructure, C69 doesn’t get the job done.

“Really, what’s going on here to a large degree is not malevolence [toward pipeline projects], it’s uncertainty. Like, genuine uncertainty from the experts,” she told Energi News in an exclusive interview. “It’s not clear in the legislation what a lot of these things mean. It’s not clear how they overlap with each other.”

“There’s also fear about how the federal greenhouse gas emissions commitments will factor in: if Alberta departs the pan-Canadian plan, will Ottawa put in situ expansion on the list of designated projects?” Bishop asks.

The Alberta government shares this concern, according to Notley, and is working behind the scenes to ensure all oil sands projects are exempted from federal assessments.

“We think that the legislation has been constructed in a way to allow for most of Alberta’s major projects to be exempted because of our work through the Climate Leadership Plan,” she said.

“That being said, It’s not 100% clear because there is language around health and socio-economic impacts, and the implications for indigenous people, and that opens the door in a way that potentially invites the Government of Canada into the process in a way that is unprecedented from the past. We’re not really sure how the two line up.”

And if the federal government has power for a carbon pricing “backstop” and the price is set to efficiently reduce emissions nation-wide, asks Bishop, why is this a relevant factor?

“The federal government has not explained how carbon pricing factors in here,” he said.

Some issues will remain uncertain until clear guidance is provided in regulations under the Act or, less firmly, in policy directives. Clarification of how to evaluate the extent to which proposed projects hinder or contribute to meeting Canada’s environmental and climate change commitments is an example, notes Gibson.

However, concern over some uncertainties by C69 critics is misplaced, he says.

“Especially on social, economic, and health assessments not often imposed under federal law, there has been plenty of experience in other assessment regimes in Canada and elsewhere, and complaints about new uncertainties are not justified,” he said.

4. Shift from environmental assessment to impact assessment

Strategic and regional impact assessments are vastly underused. We are pleased to see their prominence rise in this Bill. Strategic and regional assessments don’t look at a specific project – they look at the potential for impacts from development in general within a particular area, before a specific project application is submitted. This enables a high-level perspective to inform project-level decision-making, and is a sensible way to approach the thorny issue of cumulative effects and sustainability thresholds. – Canada West Foundation submission to Parliament, P. 4.

Olyszinski says that environmentalists wanted even stronger provisions for regional and strategic assessments.

“This is a bit of a rabbit hole but the basic idea is that looking at projects on a case by case basis is never really going to enable the effective management of multiple projects on the landscape,” he explains.

“So, regional assessments look at regions. Strategic assessments will look at a particular kind of activity, or a particular kind of harm (e.g. climate change), and try to come up with mitigation measures that can be applied systematically.”

Gibson says there are two sets of factors that will now be considered during impact assessments. The first is social, economic, health, and biophysical factors, which industry tends to think of as a red herring, while the second contribute to sustainability and long-term effects on the environment.

“While the CEAA 2012 focused on the acceptability of the project, [Bill C69] focuses on the acceptability of the adverse effects,” which is a major shift in focus for Ottawa, says the Canadian Bar Association.

There are 20 factors in total that can be considered during an assessment, including traditional knowledge of Indigenous peoples, effect on Canada’s ability to meet environmental and climate change commitments, traditional Indigenous knowledge, and the aforementioned sex and gender identity.

Industry considers some of them downright impractical.

“How do you include sex and gender identity in an analysis of an energy project?” asks Hall Findlay.

Why wouldn’t you? Olyszinski responds, pointing to the the well-documented gendered effects that a sudden influx of workers can have in remote northern communities as a practical example of a gender impact the new agency might evaluate: “Women in those communities will suffer, they will be affected by the influx of predominantly male workers in a way that is legitimately relevant to decision-makers. And I think that those effects need to be anticipated, predicted and mitigated.”

This ploughs mostly new ground for federal assessment, says Gibson, but similar considerations have been standard practice in many Canadian jurisdictions including all three territories, Quebec and Ontario since 1975. And the scope of their assessment is still subject to the discretion of the Agency or the minister and they “seem unlikely to be used often.”

Gibson says that some government and industry voices have claimed that an expectation for contributions to sustainability would mean no future project would ever be approved: “That expectation is not consistent with the historical record of sustainability-based assessment decisions, but it does speak volumes about some spokespersons’ views that their own activities are indefensibly hostile to prospects for sustainability.”

Canada would not be “doing industry any favors by not requiring it to think about climate change and how that is going to affect the bottom line, how it could potentially create financial risk but also physical risks to infrastructure,” says Dusyk.

“The provisions within C69 are not radical, but what they do say is that we need to be talking about climate change for every project.”

5. Indigenous peoples and impact assessment

The Act makes explicit what the federal Crown has already been doing under current legislation: using environmental assessment as a point-of-contact for consultation and accommodation with affected Indigenous peoples…The relationship between the duty to consult and accommodate and federal impact assessment has not been clarified by the Act and, in fact, the process appears largely the same as before. – Canadian Bar Association submission.

“These ‘new’ provisions merely recognize requirements already established in the Constitution and high court rulings,” says Gibson, who notes that the duty to consult and accommodate has bedevilled the federal government for a very long time.

“One of the challenges is that the courts have so far been reluctant to provide a substantive test because the court has a clear preference for the Crown to negotiate with First Nations communities and I think it is rightly worried that if it just comes up with a test, then you move away from negotiation towards just an application of the test,” says Doelle.

Trying to satisfy the duty to consult through the impact assessment process inevitably causes push back from indigenous communities, who for the most part don’t have the capacity to properly understand the impacts of pipeline projects on their traditional lands.

“If you encourage indigenous communities to openly participate in the assessment process and use that as a capacity building process and as an opportunity to learn about the interaction of the project with indigenous communities, and then you consulted afterward, I think you would have a much better process,” says Doelle.

Instead, it appears the federal government will bumble along much as it did under CEAA 2012, hoping the review process satisfies its constitutional obligations to First Nations, then likely having project approvals quashed by the Federal Court of Appeal, which was the fate of Northern Gateway and Trans Mountain Expansion.

The Alberta government, however, is concerned Bill C69’s consideration of Indigenous impacts will be used to intrude upon provincial authority.

“It’s not 100% clear because there is language around the health and the socio-economic and the implications for indigenous people and that opens the door in a way that potentially invites the Government of Canada into the process in a way that is unprecedented from the past and that is why we’re not really sure how the two line up,” says Alberta Premier Rachel Notley in an exclusive interview with Energi News.

“We have seen other documentation from the federal government under indigenous relations suggests they think that they have sort of an untethered ability to just march into provincial jurisdiction and completely rewrite the rules where it impacts indigenous rights and that there’s no need for the province to even be there. And so that is where there’s uncertainty that is driving our concern.”

6. Public participation

CEPA advocated for an inclusive approach to public participation, with scalable and flexible levels of involvement…CEPA’s position was that the standing requirements were reasonable for more formal opportunities such as Intervenor status, but opportunities must be provided for everyone to participate in some way. There are recent examples in Canada where the absence of a standing requirement has led to highly inappropriate participation that had no probative value with respect to the issues to be decided in the review. – CEPA submission to Parliament, P. 6.

How the public will participate in project assessments – particularly pipeline projects – is very contentious. Industry was pleased that the Harper government restricted participation with a “standing” test in CEAA 2012. The Trudeau government, however, appears to have thrown open the doors, again.

“The proposed IAA has no standing test (not even the less stringent version in CEAA 1992), which implies the full public gets in – and IAAC will need to constrain the issues in some way,” says Bishop.

Bill C-69 gives a large discretion to the new Agency or CER to determine when and how the public can participate and how to consider their input.

“The new regulator will also have to figure out how to deal with increased volume of participation in regulatory reviews,” Canada West Foundation wrote in its submission to Parliament.

“While obtaining input from a wide variety of people is a positive step, the government and/or regulator must at the same time determine how to manage a large volume of voices with similar things to say, give appropriate weight to the perspectives of those most directly impacted, and ensure that stakeholders understand that consultation does not mean veto power.”

Gibson downplays these concerns, viewing Bill C69’s provision for public participation as not much changed from the previous Act.

“While there’s to be no exclusion based on a direct interest test for standing, the inclusion may be limited to an opportunity to comment in writing, which historically has not meant having any influence,” he said.

Public participation “was curtailed in CEAA 2012 (you had to be ‘directly affected) whereas IAA swings the barn door wide open again (as it was under the original CEAA). But I’ve seen empirical research that shows that the ‘directly affected test had a minimal impact on participation, so I take this change with a grain of salt,” said Olyszinski.

7. Continuation of project list approach

Prior to the Harper government’s rewrite of the legislation, federal environmental assessments were “triggered” when federal jurisdiction was involved in some way, according to the Canadian Bar Association. CEAA 2012 introduced the “project list” that included a screening process with wider latitude that could require an assessment even if the federal government was in no way involved.

Bill C69 continues the project list approach, which the bar association supports, arguing that “it gives greater certainty on when the new impact assessment process would apply.”

But which projects make it on the list is a cause of real concern for industry. Suncor says in its submission that the criteria for adding projects must be clear and transparent. But the biggest concern echoes Premier Notley’s worry that the federal government may use C69 authority to meddle in provincial assessments of oil sands projects:

The current provincial assessment processes for in situ [oil sands] projects are robust, inclusive and acknowledge the role of the province as the life cycle regulator throughout the life of the project…In situ projects are assessed and managed adequately through environmental impact assessments, consultation, monitoring requirements and the terms of reference set by the provincial regulator.

8. Provincial concern about “jurisdiction creep”

“The main visible federal inclination, especially within the public service, is to apply the process to as little as possible. Potential expansion of coverage is possible under regional and strategic assessments, but there has been no evidence of federal inclination to proceed with regional assessments in the absence of cooperation with the relevant provincial, territorial and/or Indigenous authorities,” says Gibson.

While there may be no evidence Ottawa will meddle in provincial regulation of oil and gas, that hasn’t stopped industry from worrying.

“We recommend that exclusion criteria include how the residual risks from projects such as in situ [oil sands production] are currently mitigated, and which existing provincial and/or federal policies and regulations these projects are already in compliance with (i.e. the ability of Alberta’s Cap on GHG Emissions to meet the standards of the Federal Pan Canadian Framework),” Suncor Energy, Canada’s largest integrated oil and gas company, said in its C69 submission to Parliament.

“Acknowledging the current, robust provincial assessment processes and mitigation measures for the residual risks of projects will help to elevating(sic) public and proponent trust, while ensuring lower impact projects can remain competitive and economical for all industries.”

The one area of legitimate provincial nervousness is climate change, says Gibson, because constitutional mandates are mostly not defined and inevitably overlap.

“Sadly, climate change is a currently favoured venue for political posturing for near-term political advantage. Thoughtful and responsible discussion has been mostly absent” he said.

The Alberta government was dismayed when the NEB added downstream emissions to the review of TransCanada’s Energy East project late in 2017. The company withdrew its application, despite having spend $1.1 billion already, noting that the regulator’s decision was “the straw that broke the camel’s back.”

“We also would prefer to see a clear statement that downstream emissions are not a matter for deliberation and consideration because we have had the musings of the NEB in the past,” said Notley. “We’re almost at the point now where we want to see it articulated very clearly on the legislation.”

Gibson thinks provincial concerns may be overstated, arguing that the federal inclination, especially within the public service, “is to apply the process to as little as possible. Potential expansion of coverage is possible under regional and strategic assessments, but there has been no evidence of federal inclination to proceed with regional assessments in the absence of cooperation with the relevant provincial, territorial and/or Indigenous authorities.”

Whither Bill C69?

As of mid-Oct., the legislation sits with the Senate and will be reviewed in committee there. The Trudeau government hopes to have the legislation proclaimed and in effect by early 2019, followed by consideration of the regulations, which the relevant departments are already drafting.

Barring a major change of direction by the Liberals, sometime next year Canada will have a new environmental impact assessment system in place.

Where does that leave the Alberta-based pipeline industry? Will the predictions of CEPA CEO Chris Bloomer – that no pipeline company will ever propose a project under the C69 regime – come true?

Industry veterans like Dennis McConaghy are adamant Bloomer is right. That would be the worst case scenario.

A better scenario is that concerns raised by CEPA and the Canada West Foundation are addressed with amendments in the Senate and by the regulations.

Grant Robinson of the CD Howe Institute has several suggestions that should be seriously considered by the government.

One, slow walk the bill through the Senate until the regulations are ready. “Let’s see the full package (including the project list’) to see how the Impact Assessment Act and associated regulations will function together,” he said.

Two, phase-in the new impact assessment system, perhaps with a pilot project or two, in order to “understand the mechanics and iron out kinks with some smaller, less complex applications before extending the revamp to all major projects.”

But even if the Trudeau government follows Robinson’s advice, and even if it adopts even more amendments after the Senate review, it cannot undo the pipeline industry’s prinicpal complaint with Bill C69: removal of project assessment from the NEB.

Industry drew that line in the sand and the Liberals chose to cross it. Now we await the fallout in the oil and gas sector.

In the meantime, Jason Kenney and the United Conservative Party will continue to hold anti-C69 rallies, trying to hang the bill on Notley because of her close association with Prime Minister Trudeau and her decision to work collaboratively behind the scenes rather indulge in public criticisms.

Be the first to comment