Policies advanced by the oil sands CEOs included province-wide carbon tax, oil sands emissions cap, re-invest carbon levy revenue into innovation

Thanks to his admissions during an interview with journalist Sandy Garossino, we now know Justin Trudeau entered into a “carbon policy for pipeline” deal with Rachel Notley to get Trans Mountain Expansion built. But that wasn’t the only climate policy deal entered into by the Alberta Premier. The second time around, oil sands CEOs led the initiative, trading an emissions cap and other restrictions for no limits on crude oil production growth.

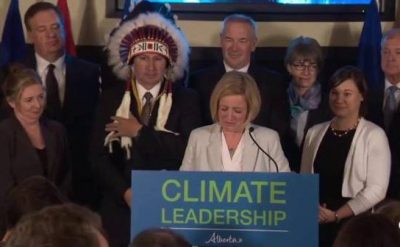

There’s a reason four CEOs from the biggest oil sands producers stood on stage with Notley Nov. 22, 2015 to launch the Climate Leadership Plan: some of the policy ideas have roots in the meetings between those very CEOs and environmental groups that began in early 2015, a few months before the election that swept the NDP to power for the first time.

For instance, Environment Minister Shannon Phillips says the idea of the 100 megatonne emissions cap for the oil sands came from the CEOs themselves.

“The emissions limit was their proposal, and we did it in to our response to the Leach report [climate change panel chaired by economist Andrew Leach] as the recommendations were being finalized because we thought that the idea had merit and because it came with a consensus attached to it with folks to whom would most apply, which is those large companies,” she said in an interview.

Phillips admits she was a bit taken aback that industry would propose the emissions cap.

“I will tell you that that suggestion, it prompted a lot of questions on my part, to the companies more than anything,” she said. “‘Are you sure you’re okay with this? This is a regulatory intervention, this is above and beyond a pricing intervention, and so on.'”

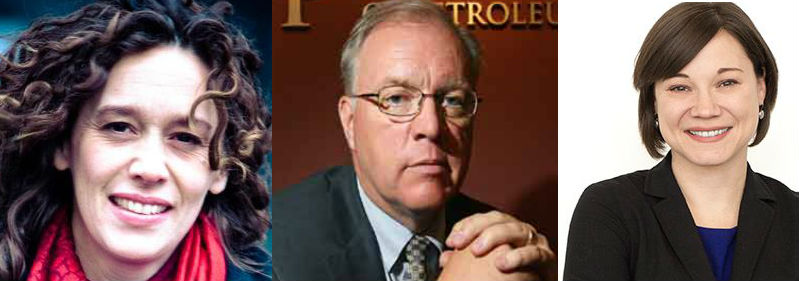

Dave Collyer is a petroleum engineer, a former Shell Canada executive, and was CEO of the Canadian Association of Petroleum Producers – industry’s chief trade and lobbying organization – from 2008 to 2014. He co-chaired the informal meetings between the five oil sands CEOs and the five environmental groups with Tzeporah Berman, who represented the ENGOs.

Collyer says that industry’s goal was to avoid a cap on production, which in the latest CAPP supply forecast is set to rise by 2 million b/d by 2035 from it’s current level of 2.7 million b/d.

“The climate plan includes an emission limit which provides for significant growth of oil sands production, keeping in mind it’s an emissions limit, not a production limit, so more growth in production if industry can in fact reduce the emissions-intensity [of heavy crude oil], and that production growth requires new pipelines,” he said in an interview.

Phillips confirmed Collyer’s point: “Another piece of the consensus that came from those groups that then came to us in early Sept. 2015 was this notion of a limit on emissions, not a limit on production.”

“We were even able to reach an agreement that, yes, there should be a cap on emissions which also stimulates competition and innovation and gives certainty from an industry perspective. And from an environmental perspective, it also provides certainty,” Berman said in an interview. “In the end, it really felt to me like a lot of our conversations came down to what could provide greater certainty.”

The idea of limiting emissions but not production would eventually be the issue that soured Berman on her work co-chairing the Oil Sands Advisory Group – with Collyer and Melody Lepine – that led to her increasingly vocal opposition to the oil sands and more pipelines in the British Columbia media, which in turn caused tension with the Alberta government and her fellow OSAG members.

But the 100 Mt emissions cap wasn’t the only chip industry threw on the bargaining table.

The CEOs and ENGOs “also came with the methane [emissions reductions] recommendations. As I recall, their original recommendations were less than what we ended up doing because it was felt that the companies they could actually up their level of ambition if given an appropriate offset protocol and a time period to monetize that offset value,” Phillips said.

Another climate policy piece advanced by the informal coalition was that “funds from large final emitters ought to be reinvested into clean tech and innovation and so on,” according to the environment minister.

The final recommendation, one that has been harshly criticized by UCP leader Jason Kenney, is the economy-wide carbon tax.

“Things were moving very quickly [during the summer of 2015] because a lot of the conversations had already been had between key environmental groups and oil sands companies around a couple of different topics. One was the necessity of having an economy-wide [carbon] price structured similarly at its levels to British Columbia,” she said, adding that industry also favoured a policy mechanism – which later became the Carbon Competitiveness Incentives Regulation – to protect emissions-intense, trade-exposed industries like the oil sands.

“We were able to find much more common ground in some places than we thought, around carbon pricing and around a number of other issues,” says Berman.

“The bottom line is that some of the key policies that are now in the Alberta climate plan like carbon pricing which actually helps the industry in the long-term, it also helps the environment because it reduces emissions and pollution.”

Phillips points out that some of the joint CEO/ENGO ideas were already being considered by Prof. Leach’s climate change panel.

“As I always say about climate policy, it’s difficult and the questions are many but the answers are actually relatively few,” she said. “You price emissions and then you’ve only got so many mitigation options and then you have some adaptation options and some technology options.”

The oil sands CEOs were clearly determined to have as much influence as possible over which policy options the Notley government chose and how those policies were implemented.

But they also understood the value of maintaining and leveraging the relationships formed with the ENGOs, which is why they were supportive of the government appointing Berman as one of the three co-chairs of the The Oil Sands Advisory Group.

“I can’t remember who said it but I can remember one meeting where they [the CEOs] said, ‘It’s not going to work unless you’re going to agree to co-chair it.’ So, we had a very cordial relationship and they really wanted us there,” she said.

That cordial relationship endured until the West Coast-based activist realized that the CEO’s coveted pact to grow production was never going to be consistent with Canada’s Paris emissions reductions targets.

In the next column, we’ll explore how Berman’s activism frayed her relationships in Alberta and what she thinks about CAPP’s recent climate policy study, which she believes demonstrates that the oil sands CEOs are not committed to serious emissions reductions.

Be the first to comment