American investors are picking up discounted shale oil and gas assets on the cheap, preferring them to long-cycle oil sands investment, say US economists

Oil and gas investment is falling in Alberta and rising rapidly in US shale basins. Is this a sign that Alberta can’t compete for capital, as industry groups allege? While Alberta certainly has issues affecting investor confidence, such as insufficient pipeline capacity, two American economists say there is something unique going on in the United States, especially the prolific Permian Basin.

Tim McMillan is the president and CEO of the Canadian Association of Petroleum Producers and he told Energi News last month that “we look globally and we’ve seen capital flooding back into the energy sector.”

Tim McMillan is the president and CEO of the Canadian Association of Petroleum Producers and he told Energi News last month that “we look globally and we’ve seen capital flooding back into the energy sector.”

Calling it a “flood” might be a bit over the top.

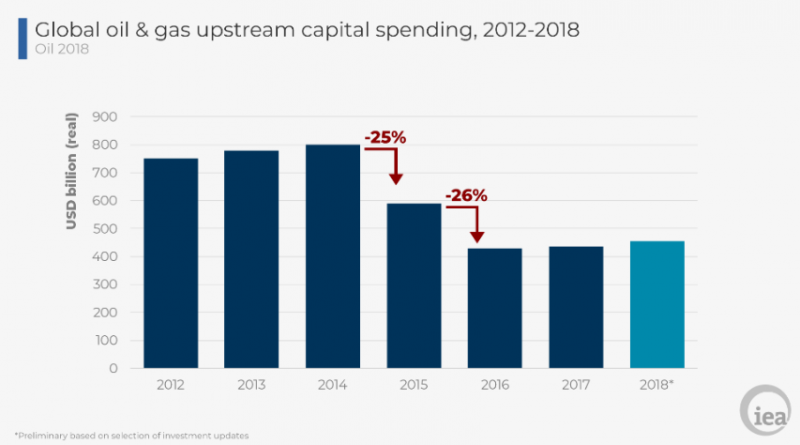

The International Energy Agency’s most recent oil report shows that after hitting a peak of $800 billion in 2014, global upstream capital spending fell to just over $400 billion in 2016 and hasn’t really recovered, with 2018 investment forecast to be $450 billion.

Global investment may be stagnant, but the latest survey from the Oil & Gas Journal estimates this year’s US oil and gas upstream capital spending will rise nine per cent to $184 billion. Canada will mirror international trends, struggling to reach $40 billion (conventional estimate is $28.6 billion, with the oil sands clocking in at just $11.4 billion).

McMillan is partly right when he says that Canada’s capital expenditure issue is caused by “difficulty to get access to markets for our products” and “the number of regulatory costs and changes that are underway and being implemented in Canada today is inconsistent with countries we’re competing with for capital, and those costs continue to escalate here while other places have very active programs to streamline and find efficiencies.”

But there’s another reason capital is easy to come by in the US: bargain hunting.

According to University of Houston energy economist Ed Hirs, shale assets can be picked up for “less than the replacement costs.”

Shale basin producers, with their rapid production declines, have have been propped up by Wall St. during years of unprofitable operation.

“Small and medium-size independent producers, which dominate the US shale industry, generally have much higher leverage with high levels of debt and hedging,” Alessandro Blasi and Yoko Nobuoka of the IEA wrote in Energi News Thursday. “Since its inception, the industry has been characterized by negative free cash flow as expectations of rising production and cost improvements led to continuous overspending in the sector.”

That appears about to change.

For the first time, in 2018 shale appears poised to actually make a buck and that has the Wall St. wolves circling the herd looking to pick off the weak and vulnerable, according to Hirs.

“There’s new money coming in in terms of equity but what they’re doing is they’re still buying up the first guys that were there at a discount,” he said in an interview.

Starting fresh in the Permian Basin where land costs of up to $65,ooo an acre have been reported is an expensive proposition, say Hirs. The smart money is looking for struggling companies that have the potential to thrive now that oil prices have recovered (West Texas Intermediate closed just under $70USD on Friday).

“It’s an opportunity for investors to buy what appears to be the great new asset in the oil patch in the US at a discount to what it was costing 18 or 24 or 36 months ago,” Hirs said. “With oil prices at $60 to $70 barrel, folks can make the Permian work.”

A great opportunity coupled with a lack of opportunity in the rest of the global industry, says Raoul LeBlanc, an energy economist with IHS MarkIt’s Houston office.

“The rest of the world is generally not open for business,” he said in an interview. “Companies like BP or other foreign new entrants, they’re getting in because shale represents the opportunity for them to buy production reserves in a low-risk area. It’s scalable: you can dial it up or dial it down any time and there’s a lot of growth potential.”

LeBlanc says the oil sands are a completely different business model, one that requires a deep understanding of the resource and the required extraction methods, and patience to be invested for the long haul.

“The oil sands is a game that I have to be very committed to. It’s got a lot of factors that are beyond my control, like the pipeline situation, and it’s a very specific game among a very few companies,” he said.

“The resource is enormous, of course, but it’s high cost and you can’t grow production very fast, and you don’t have any flexibility. Once you’re on this thing, you’re on it for 20 to 25 years.”

Wall St. prefers the fast buck.

“I think these guys like the short-cycle barrels that they’re able to get from US – and Canadian shale, too. Shale gives you modularity and flexibility in a way that you don’t get from offshore or the oil sands,” he said.

Dinara Millington, head of research for Calgary-based Canadian Energy Research Institute, agrees with LeBlanc.

“Even within Canadian borders, spending is now directed more towards condensate and tight oil plays. Not to say there is no capital being spent in oil sands, however, oil sands-related expenditures are geared to sustaining and expanding existing projects,” she said in an email.

She ascribes the Tsunami of capital flowing into US shale basins to “shorter business cycles for expected return on investment and smaller initial capital outlay requirements are the main drivers. Other motivating factors include recent tax reform in the US, less environmental stringency, and wider access to overseas markets.”

So, at the very least, the question of Canadian oil producers’ ability to compete for capital is much more complex than McMillan and industry players commenting in the media would have Albertans believe.

Ben Dachis, an economist with the CD Howe Institute, recently took a representative well and calculated policy costs for that well in various Canadian and American jurisdictions. His conclusions put a different spin on CAPP’s argument about regulatory costs.

“Canadian energy producers are at a competitive disadvantage relative to producers in the United States. Much attention has been paid to carbon taxes, but a lack of market access for oil and taxes on investment – not emissions prices – are the main policy-induced competitiveness problems for conventional energy producers in Western Canada,” said Dachis.

Market access – i.e. more pipelines – is exclusively federal jurisdiction and the responsibility of Prime Minister Justin Trudeau, not Alberta Premier Rachel Notley. As for US bargain hunting for shale basin assets, Hirs expects that to last six months to a year, 18 months at the outside.

While these problems are being addressed in Canada or are resolving themselves south of the border, Albertans should be skeptical of simplistic claims that any government is wholly to blame.

The political silly season has arrived early this election cycle and it should come as no surprise that energy issues like competitiveness are being torqued for political gain.

Be the first to comment