Inability to fully load larger and more cost-effective vessels has pricing implications for US crude oil exports

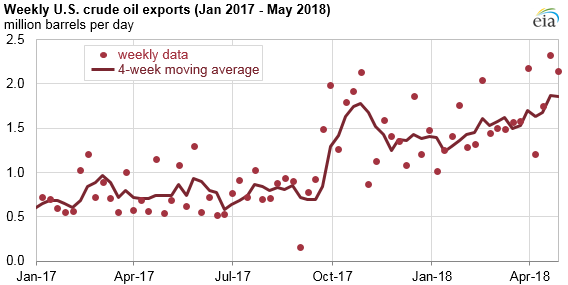

U.S. crude oil exports averaged 1.1 million barrels per day (b/d) in 2017 and 1.6 million b/d so far in 2018, up from less than 0.5 million b/d in 2016, according to the U.S. Energy Information Administration.

This growth in U.S. crude oil exports happened despite the fact that U.S. Gulf Coast onshore ports cannot fully load Very Large Crude Carriers (VLCC), the largest and most economic vessels used for crude oil transportation. Instead, export growth was achieved using smaller and less cost-effective ships.

Each VLCC is designed to carry approximately 2 million barrels of crude oil. Because of their large size, VLCCs require ports with waterways of sufficient width and depth for safe navigation. All onshore U.S. ports in the Gulf Coast that actively trade petroleum are located in inland harbors and are connected to the open ocean through shipping channels or navigable rivers.

Although these channels and rivers are regularly dredged to maintain depth and enable safe navigation for most ships, they are not deep enough for deep-draft vessels such as fully loaded VLCCs.

To circumvent depth restrictions, VLCCs transporting crude oil to or from the U.S. Gulf Coast have typically used partial loadings and ship-to-ship transfers. The ship-to-ship transfer process known as lightering refers to a larger vessel partially unloading onto a smaller vessel.

Reverse lightering occurs when smaller vessels load onto a larger vessel. These transfers take place in designated lightering zones and points that exist outside many of the largest U.S. petroleum ports.

Data from the U.S. Maritime Administration (MARAD) for 2015, the latest year for which data are available, indicate that the two largest ports of call for tankers carrying crude oil and petroleum products in the United States are lightering zones.

The South Sabine Point and Southtex lightering zones each had nearly 250 million deadweight tons of tanker traffic volume in 2015. Deadweight tons are a measure of a vessel’s capacity to carry cargo by weight. The number of barrels per ton varies based on the density of the petroleum product or crude oil cargo.

Currently, most U.S. Gulf Coast petroleum ports are capable of accepting vessels with capacities of approximately 500,000 barrels of crude oil (AFRAMAX). The number of ports that can accept vessels with capacities of approximately 900,000–1,000,000 barrels (SUEZMAX) is relatively limited. Four AFRAMAX-sized vessels or two SUEZMAX-sized vessels are required to carry the same amount of crude oil as a single VLCC.

The inability to fully load larger and more cost-effective vessels has pricing implications for U.S. crude oil exports. Using a number of smaller ships requires a wider price spread between U.S. crude oil and international crude oil prices to compensate for the lower economies of scale and costs associated with reverse lightering and partial loadings.

The costs associated with using smaller vessels are less of a factor for exports over shorter distances. However, as exports to Asia are a growing share of total U.S. crude oil exports, these costs will become more important.

By comparison, other nations that export large volumes of crude oil generally have deeper and wider navigable waterways that are not located in inland/onshore harbors. For example, in Yanbu, Saudi Arabia, located along the Red Sea, the crude oil export facility uses a jetty trestle that extends out to berths in water deep enough to fully load VLCCs.

The Louisiana Offshore Oil Port (LOOP), located offshore southern Louisiana in the Gulf of Mexico, is currently the only U.S. facility able to accommodate a fully loaded VLCC. LOOP, which has storage, undersea pipelines, and single-point mooring facilities in deep water, was exclusively used as an import facility until it was modified to allow exports earlier this year.

Weekly U.S. exports of crude oil have surpassed 2 million b/d four times so far in 2018, and trade press reports indicate two of those instances—the weeks of February 16 and March 30—corresponded with weeks in which LOOP loaded a VLCC for export.

MARAD, the agency charged with permitting deepwater offshore ports, currently has no pending applications for new deepwater ports similar to LOOP. Instead, trade press and company announcements have indicated the most likely crude oil export projects with the intention to fully load VLCCs will be located near the port of Corpus Christi in southern Texas.

Corpus Christi has access to increased domestic production of light-sweet crude oil from the Permian Basin and Eagle Ford and regularly exports crude oil from the Oxy Ingleside Energy Center and other facilities.

Be the first to comment