Canada needs a hydrocarbon “moonshot” – John F. Kennedy’s 1961 vow to put a man on the moon by 1970 – to refocus the oil/gas sector from fuels to materials

Click here to read and sign The Energi Declaration: An optimistic, moderate vision of Canada’s energy future

Click here to read Markham’s column about why Canadians, not industry, should lead a national conversation about energy

The Canadian oil and gas sector, beset by threats from many sides, has arrived at an important juncture in its history. The status quo is unacceptable. Tepid change in the face of the energy transition and the climate crisis is also unacceptable: business as usual with minor tweaks as the global energy system is transformed is neither good business strategy nor the most productive use of publicly owned natural resources. The time has arrived for Canada to think differently about hydrocarbons and to be hugely ambitious.

The list of industry challenges is long: the COVID-19 recession and uncertainty over the post-pandemic economy; volatile global markets; the federal government’s determination to apply stricter climate policies to the industry that creates 23 per cent of national emissions; pipeline projects obstructed by indigenous communities, landowners, and environmental groups; high cost of capital due to climate risk; a junior sector in dire straits; low natural gas prices caused by the expansion of US shale producers into Eastern Canadian markets.

Even if the global economy recovers from the pandemic recession later this year or in 2021, many questions remain about how the disruption will affect future energy consumption. Will more people work from home? Will airline travel return to previous levels? Will governments see the pandemic as an opportunity to enact tough policies that restrict burning hydrocarbons?

The most dangerous existential threats of all, however, are the energy transition and climate crisis. They are driving profound structural changes in global energy markets that will likely begin destroying demand for hydrocarbons sometime this decade. The overarching message of The Energi Declaration is that the transformation of the global energy system isn’t coming, it’s here already, it’s accelerating, and Canada must pivot much more quickly to the low-carbon economy of the future.

How does this apply to the hydrocarbons sector?

Oil and gas production plays an outsized role in the Canadian economy. Hydrocarbon production can’t simply be stopped (“keep it in the ground”) or be phased out without serious economic consequences. Nor, given the disruptive changes that have already begun, can the oil and gas provinces blithely assume a best-case scenario of rising consumption, peak oil demand several decades out, then a slow decline, giving the industry plenty of time to adapt (“drill, baby, drill”).

A new approach is needed. The Energi vision for hydrocarbons imagines a two-pronged strategy.

One, Canada and the hydrocarbon industry must quickly commercialize processes that use hydrocarbon feedstocks for non-combustion purposes like making carbon fibre from bitumen and zero-carbon fuels like hydrogen from natural gas. Manufacturing new products instead of shipping raw hydrocarbons not only diversifies the markets for Canadian oil and gas, but can also add significant value; for example, Alberta Innovates estimates that a barrel of bitumen turned into carbon fibre is worth 1.5 to 2.5 times the value of a barrel sold to a refinery.

Two, in anticipation of peak oil demand and declining fuel markets, oil and gas companies must accelerate the decarbonization of their oil and gas production (absolute emissions are still rising), the reduction of production costs, and the improvement of their environmental performance (37 giant tailings ponds, orphan wells, high methane leak rates, for example). As long as Canada sets the bar higher and Canadian producers meet those standards, they should be granted the social license to fight for the biggest possible share of shrinking markets as long as there is demand for heavy crude and natural gas.

Two, in anticipation of peak oil demand and declining fuel markets, oil and gas companies must accelerate the decarbonization of their oil and gas production (absolute emissions are still rising), the reduction of production costs, and the improvement of their environmental performance (37 giant tailings ponds, orphan wells, high methane leak rates, for example). As long as Canada sets the bar higher and Canadian producers meet those standards, they should be granted the social license to fight for the biggest possible share of shrinking markets as long as there is demand for heavy crude and natural gas.

Adapting to disruption

Imagine it’s 2050, the year Canada has set to become a net-zero emission economy. What will the energy world look like in 30 years? The answer is important because that’s the future the Canadian hydrocarbon industry and governments should begin preparing for today.

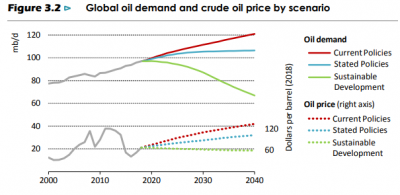

The IEA models scenarios of the energy future. The “stated policies” scenario sees global oil demand plateauing a few years from now and remaining flat until 2040, while natural gas grows from 4 Billion cubic metres per day (bcm/d) to 5.4 bcm/d. The “sustainable development” scenario has oil consumption declining rapidly to 65 million barrels per day and natural gas not rising at all.

Canada’s strategy to 2050 should be to act as if the sustainable development scenario is most likely. Why? Because the status quo is unacceptable. The Canadian industry has feet of clay. Instead of looking forward to a disrupted, low-carbon world increasingly powered by renewable electricity, the sector is stuck in a backward-facing status quo. It is out of step with the global energy transition, the climate crisis, Canadian energy and climate policy, and Canadian public opinion.

For example, every major oil and gas company (Shell, BP, and others) that reviews their membership in national industry associations finds the Canadian Association of Petroleum Producers (CAPP) “misaligned” on climate policy. A leaked copy of CAPP’s 2020 COVID-19 submission to Ottawa shows it was mostly a laundry list of environmental and climate regulations the organization wanted rolled back, delayed, or cancelled. No surprise, the federal government denied all of CAPP’s requests.

The issue is leadership. The current crop of leaders is hyper-partisan, tribal, and wedded to political and communications strategies better suited to the 1980s. Instead of taking their cues from the progressive European majors like Shell and Equinor, they admire the regressive approach of the Permian Basin shale producers in West Texas. Canadians, on the other hand, overwhelmingly approve of the transition to “clean energy” and expect public policies to support the change.

The Alberta-based oil and gas industry needs new leaders, strategies, and narratives that align the sector with the energy transition, climate change, and Canadians’ expectations for the future of energy.

A post-combustion narrative

Assuming the sector can resolve its leadership crisis and persuade Canada to support long-term oil and gas production for shrinking markets, over the next 10 years Canada should invest heavily to bring current post-combustion research to market. The goal must be the rapid commercializing of new hydrocarbon-based products and manufacturing processes.

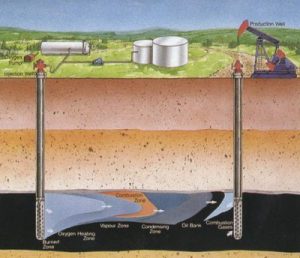

The federal and Alberta governments must take the lead. Fortunately, there is a model for them to follow. Peter Lougheed invested $1.4 billion (today’s dollars) in the Alberta Oil Sands Technology and Research Authority (AOSTRA) to develop and commercialize the steam-assisted gravity drainage extraction model for in situ oil sands. Today, SAGD production sits at 1.75 million barrels per day and is expected to almost double by 2040.

“The lessons learned nearly half a century ago can still stand the province in good stead even though the challenges for the oilsands and the province look nothing like they did in the 1970s,” Dr. Sara Hastings-Simon in a 2019 paper.

Lougheed shouldered most of the financial burden, but an explicit post-combustion strategy by industry and Alberta would almost certainly attract significant funding from Ottawa, which appears determined to meet Canada’s 2050 net-zero emissions promise, if not the 2030 Paris agreement targets. The economic and tax benefits alone are a good argument for Ottawa to bear much of the cost of transitioning to a post-combustion industry.

Will Canadians support those investments?

Public opinion polling shows there is little appetite across the country – with the exception of Alberta and Saskatchewan – for subsidizing the status quo. Canadians overwhelmingly expect the economy to use far fewer hydrocarbons in 30 years. They expect public policy to support the transition off fossil fuels. There is also considerable support for the promotion of clean energy industries.

Post-combustion narratives that incorporate the energy transition and climate change stand an excellent chance of persuading Canadians to back a long-term future for the hydrocarbons sector.

The post-combustion strategy

The goal of a post-combustion strategy would be to battle hard for market share in declining fuel markets while simultaneously developing and investing in new manufacturing processes that use bitumen and natural gas as inputs. As one falls, the other rises, creating new jobs and business opportunities for Canadians.

Will industry executives support a moonshot strategy – achieving net-zero emissions, better environmental performance, and the commercialization of post-combustion processes – by 2030? Almost certainly not.

The oil and gas industry is incredibly risk-averse because failure comes at a high cost. Companies are run by engineers who are trained to not fail. Engineers may be incredibly innovative “within the box,” but they are extremely conservative when asked to innovate outside the box or, worse yet, to change the box. Oil and gas corporations are imbued with an engineering culture. Supporting industries like services and finance are the same.

This is why governments and civil society groups like progressive business organizations and unions – but not hydrocarbon critics supporting “leave it in the ground” or the “drill, baby, drill” boosters – must play a leading role in a post-combustion strategy. Instead of a battleground, Canada needs a moderate, pragmatic approach that can find common ground and a way forward.

Five post-combustion tactics

Fortunately, research has been going on for some time on post-combustion products, decarbonizing oil and gas production, and technology innovation. A robust innovation network funded by Ottawa and several provinces is already in place. Industry, especially the large oil sands companies, spend hundreds of millions each year on research and development. Finally, university researchers at the Universities of Alberta and Calgary, as well as in other provinces, have been working on some post-combustion-style issues for decades.

The point being that Canada is already midway along the journey to post-combustion. The question is not so much of doing things differently as of doing much, much more of what is already being done.

The five post-combustion tactics suggested below require new ways of thinking on the part of industry and government, political commitment to change, and plenty of financial support.

- Canada competes for whatever remains of the global heavy crude oil market for fuels, petrochemicals, and asphaltenes by becoming cost and carbon-competitive, while significantly improving the industry’s environmental performance.

By mid-century, the heavy crude market could be 1 million barrels per day, the same, or even bigger. The smart bet, however, is to assume it will be much smaller and to prepare to compete ferociously with the Latin American producers like Brazil, Mexico, and perhaps even Venezuela. To some extent, the oil sands companies are already doing that. They talk about producing the “best barrel,” becoming “cost and carbon-competitive,” and achieving net-zero emissions by 2050.

Admirable goals, but they must decarbonize their production processes faster. Much faster. By 2030 or, at the latest, 2040. Disruption, by definition, is uncomfortable, and Canada cannot wait while the oil sands companies proceed at a pace that’s comfortable for them.

How might they decarbonize? Suggestions include:

- Electrify production processes using renewable energy. Small modular nuclear reactors, as was suggested in the federal government’s Generation Energy Council report two years ago, should also be considered.

- SAGD production substitutes solvents for steam.

- Mining adopts new technologies like CNRL’s IPEP.

- Ottawa backfills cancelled Alberta’s cancelled $2.1 billion partial upgrading program.

2. Bitumen and conventional heavy crude oil become feedstock for materials production

Alberta Innovates is leading the research into “bitumen beyond combustion.” A 2018 study identified the following products as having potential:

- Carbon fibre: a composite material that is very light and strong, but expensive. A barrel of bitumen made into carbon fibre yields 1.5 to 2.5 the value compared to being refined into fuel. Alberta Innovates estimates that commercial production from bitumen is five to seven years away.

- Flow batteries: vanadium is used to make flow batteries that store electricity from wind and solar generation. Vanadium is plentiful in bitumen.

- Asphalt: even in a post-combustion world, roads will be built and repaired. Bitumen makes excellent asphalt and could serve a global market if researchers can find a way to transport it at ambient temperature (no heating required).

Additional potential post-combustion products related to hydrocarbon production include petro-lithium and rare earth minerals.

3. Canada competes for whatever remains of domestic natural gas and LNG export markets

Because the carbon-intensity of natural gas is half that of coal, the IEA expects substantial demand for gas to last well into next century. The problem for Canada is that the rest of the world produces an enormous quantity of gas. The domestic sector is already distressed, pushed out of markets in Eastern Canada by shale producers in the Northeast United States, pipeline bottlenecks have caused serious problems, and prices have been persistently low for years.

Nevertheless, Canadian are efficient, low-cost producers who will no doubt remain competitive for a long time. If global LNG markets expand as expected, Canadians should be encouraged to pursue those markets. This should include construction of pipelines and other infrastructure.

4. Canada processes natural gas into “blue hydrogen” and petrochemicals

Petrochemicals: Alberta is already home to the second-largest petrochemical complex in Canada. Alberta’s Energy Diversification Advisory Committee identified the cost of capital as the biggest obstacle to expanding this sector. The provincial government’s Petrochemicals Diversification Program provides “royalty credits to companies in exchange for building facilities that turn ethane, methane and propane feedstocks into products such as plastics, fabrics and fertilizers.” Additional federal funding of this program and more aggressive marketing by Alberta could attract significant investment as Asian demand for plastics grows over the next two decades.

Blue hydrogen: made from natural gas, with emissions sequestered underground. Supporters believe hydrogen is the future’s clean fuel for long-distance freight hauling, home heating, and industrial processes that require high heat. There are still many obstacles to the wide-spread use of hydrogen, but significant strides are being made and the Canadian government should increase its support for this promising industry. Green hydrogen, made from renewable electricity using electrolysis, has potential in the longer-term as Canadian communities build out wind and solar farms that generate cheap and plentiful power.

5. New markets for oilfield technology

Alberta, in particular, is home to a vibrant oilfield manufacturing and technology sector. This includes software, sensors, and pumps, among many other types of products. The opportunity exists to expand the sector in two ways. One, help Canadian firms tap other oil and gas markets around the world. Two, find non-energy industries where the technology has applications.

The 2050 hydrocarbon vision in action

By mid-century, but preferably sooner, the Canadian oil and gas sector must be low-cost, efficient, competitive in declining markets, a true environmental leader, and a supplier of feedstock to non-combustion markets across the country. This vision should not be optional or aspirational, it should be the minimum required of the hydrocarbon sector in return for support from Canadians and their governments.

In fact, think of it as a pact between the oil and gas industry and Canada. If industry leaders and their political supporters in Alberta shake hands with Canada, agreeing in good faith to achieve the new hydrocarbon vision as quickly as possible, then Canada must also act in good faith to help the industry meet the new goals. If the sector balks or drags its feet, then the deal is off.

The benefits of making and sticking to the deal are potentially significant for both parties.

For Canada, a post-combustion hydrocarbons strategy preserves the country’s largest export industry, attracting capital and creating jobs while doing it with an environmentally sustainable business model.

For the industry, and Alberta in particular, such a strategy has the potential to extend the life of the oil sands well into the next century, even if only as the supplier of feedstock to non-combustion manufacturing, which could possibly require more bitumen than is currently being refined for fuel; time will time on that count. In addition, commitment to post-combustion may finally earn the industry the social license it desperately needs to remain viable long-term.

There is one additional benefit: the federal government’s commitment to achieving net-zero emissions by 2050 is on a collision course with Alberta’s current oil and gas ambitions. That conflict must be resolved. The hydrocarbons industry and Alberta agreeing to pivot to a post-combustion approach would be an excellent start.

Industry supporters often dismiss the need for an energy vision. They prefer plans, especially when the oil and gas sector is managing multiple crises, as it has been since 2014. “Fix our problems, then we’ll talk,” is their attitude.

The supporters are dead wrong.

Canada must start with a new vision for the hydrocarbon future. Then, narratives and stories to back them up can be employed to engage Canadians (not providing lists of facts and data, which has long been the industry’s ineffectual approach) and build support for the new vision. Once Canadians are on board, plans can be drawn up that Canadians will support and governments will help fund and facilitate with legislation and regulations. Canada must step up financially in a big way, investing as many billions as required.

A post-carbon industry restructured to focus on materials instead of fuels can be Canada’s “moonshot.” When John F. Kennedy declared in 1961 that the United States would put a man on the moon before the end of the decade, it seemed an impossible task. Against all odds, NASA fulfilled his vision a year early. That’s the kind of vision required of Canadian oil and gas leaders and our nation’s politicians.

If Canadians are to have hope and optimism in the future of the national hydrocarbon industry, a post-combustion approach is the only way forward.

Be the first to comment