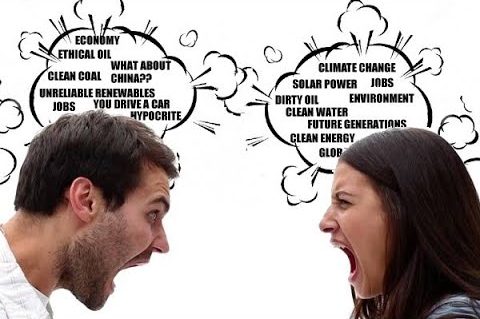

The Canadian energy conversation is dominated by two camps: “leave it in the ground” and “drill, baby, drill.” Both represent a small minority of Canadians. With the energy transition speeding up and the climate crisis worsening, Canadians need a third option: a moderate and pragmatic vision for the future that stresses pivoting to the low-carbon future while preserving those parts of the hydrocarbon sector that make sense in a clean energy economy.

The Canadian energy conversation is dominated by two camps: “leave it in the ground” and “drill, baby, drill.” Both represent a small minority of Canadians. With the energy transition speeding up and the climate crisis worsening, Canadians need a third option: a moderate and pragmatic vision for the future that stresses pivoting to the low-carbon future while preserving those parts of the hydrocarbon sector that make sense in a clean energy economy.

The Energi Declaration is meant to be that vision. Chapters will be added to apply the Declaration principles to Canadian energy sectors and issues.

Chapters:

Please support it by signing the form below, then share the Declaration link with your family, friends, and social media network and ask them to sign it. Together, we can change Canada’s energy conversation.

Sign to show your support!

Together we can change the Canadian energy conversation!

The 12 Energi Declaration Principles

- Acknowledge that the energy world is rapidly changing and that maintaining the Canadian energy status quo is not good enough. How we think and talk about the energy transition influences our resolve to plan and act. Reject polarizing energy narratives. Support moderate, pragmatic, solutions-oriented approaches to Canada’s energy future. Be optimistic about Canada’s energy future.

- Embrace the energy transition. Acknowledge that new energy technologies like wind and solar, battery storage, hydrogen, and EVs are driving structural change in energy markets. Enormous capital investments over the past 20 years, changing consumer preferences, and public policy have made that change self-sustaining. While the scale and complexity of the global energy system make the timing uncertain, the transition from fossil fuels to electricity generated by low-carbon technologies is inevitable.

- Embrace climate science. Acknowledge that global warming is caused by human activity, that climate change is a serious threat to our planet’s ecosystem and our way of life. Support robust national climate policies. Provinces setting the climate policy bar at the lowest level possible must step up and commit to national standards. Think of climate policy as the “accelerator pedal” of the energy transition – step harder on the policy pedal and the transition speeds up.

- Acknowledge that economic risk from the energy transition and climate change is here now. Take steps to mitigate risk. Hope for a long runway to adapt, plan for a short one.

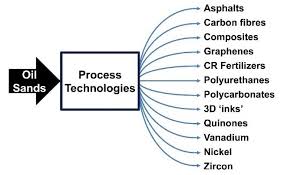

- Acknowledge that abundant economic opportunities are being created by the energy transition. Recognize the significant innovation already occurring within Canada’s energy economy and support policies that increase innovation. Innovation is key to attracting investment and creating the jobs of the future. Significantly expand research into “bitumen beyond combustion” – using bitumen as a feedstock for the manufacture of products like carbon fibre – and invest in the rapid commercialization of those products to help Canada gain an early competitive advantage as new markets emerge.

- Commit to a more rapid build-out of renewable energy. Abundant cheap electricity is a significant competitive advantage in the low-carbon economy. Support electrification and hydrogen systems for transportation, buildings, and industry (including the production of hydrocarbons).

- Commit to constitutional conferences as called for in Section 35 of the Constitution Act of Canada, 1982 to negotiate a resolution of aboriginal land title and indigenous law issues with the indigenous peoples of Canada. As part of the reconciliation process, empower them to become significant equity owners in the Canadian energy industry. With ownership will come economic reconciliation.

- Acknowledge that technology is changing the nature of energy work. There are fewer good-paying oil and gas jobs. Lost jobs are not coming back; investment in new energy industries is needed to replace those jobs. Jobs are becoming more technical, with a strong data component, which will require re-skilling. Unions must play an active role in training the energy workers of the future. Canada must remain committed to the right to organize and “unions of convenience” should not be used to bar workers from union membership. Energy projects should be built using Community Benefits Agreements.

- Acknowledge that oil consumption will begin to decline within 10-20 years. Commit to being cost and carbon-competitive within the 10 million barrels per day global heavy crude oil market. Commit to the “best barrel” principle. When the last drop of decarbonized heavy crude oil is processed into fuel on this planet sometime in the future, let it be an Alberta drop.

- Acknowledge that natural gas peak demand may occur long after oil consumption has begun to decline. Continue pursuing the lowest possible methane leakage rates from the production, gathering, and transportation systems, including the electrification of gas production and liquefaction. If Canada can produce low-emission natural gas, it can manufacture “green LNG” and “blue liquid Hydrogen.” Support the construction of new hydrogen infrastructure, including fueling stations and pipelines across Canada. Support expansion of non-combustion uses for natural gas, such as petrochemicals.

- Make non-pipeline strategies the first resort for expanded heavy crude oil market access and new pipelines the last resort. Restore public support for bitumen partial upgrading technologies, which could free up hundreds of thousands of barrels per day of shipping capacity from existing pipelines. Accelerate adoption of non-pipeline shipping of bitumen by rail, like DRUbit and Canapux.

- Commit to significantly improving the environmental performance of hydrocarbon production. This includes implementing a robust oil and gas liability management system. Ensure orphan wells do not become a burden on the taxpayer. Ensure oil sands tailings ponds are reclaimed in a timely manner. Ensure absolute oil and gas GHG emissions – not just emissions-intensity per barrel – begins to decline in the near future; particular emphasis should be placed on lowering oil sands emissions.

Join 255 others in signing The Energi Declaration

Evidence for why the Energi Declaration vision makes sense

Several decades into the current energy transition and we now have enough evidence to imagine the energy future. What does it look like? In a word, amazing. Fossil fuels will mostly – but not entirely – be replaced by electricity generated with low carbon technologies like wind and solar. Electrified cars and trucks, homes and commercial buildings, and industrial processes like steel foundries mean higher efficiency, less waste, and lower cost. In theory, electrifying the global economy should also lead to a cleaner environment.

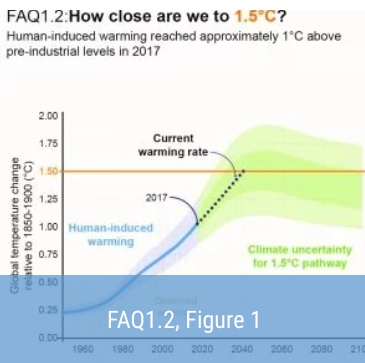

Will enough progress be made to keep the global temperature rise to 1.5C or 2C by 2100? The bad news is that current trends suggest not. The good news is that with the energy transition ready to leap ahead during the 2020s, humanity at least has a shot at making 2050 Paris Agreement targets.

It’s hard not to be sympathetic to environmental groups’ demands that hydrocarbon production growth be stopped immediately, followed by an orderly phaseout. The climate crisis is an existential threat to humanity. There are cost-competitive clean energy alternatives to fossil fuels. Two arguments, however, make the case for not “keeping it in the ground.”

One, energy transitions take a long time, generally 50 to 100 years. Even if we argue that the modern transition will be faster because of scientific advances and rapid technology improvements, how much it can be accelerated with climate policies is highly uncertain. Persuading consumers, workers, and governments to deliberately wind down a competitive industry without readily available replacement technologies will be difficult.

Speeding up the energy transition will be tough and there’s no point pretending otherwise.

Two, there will likely still be some level of demand for heavy crude oil and natural gas in a low-carbon economy, both as fuels and as inputs for non-combustion manufacturing. If there is, why shouldn’t the future Canadian oil and gas sector – whose production is truly decarbonized and with significantly improved environmental performance – capture those economic benefits for the benefit of Canadians?

Imagining a future without fossil fuels doesn’t preclude a future in which oil and gas are used for other, higher-value purposes.

Successfully pivoting to that low-carbon future will be difficult, however, if a significant portion of Canadians is afraid of change that cannot be avoided or stopped.

Conservative populists seem convinced that the upheaval of recent years is just another boom-bust cycle, not the beginning of a structural transformation of the global energy system. They view energy through a political lens: if the parties with the wrong ideology can be replaced by parties with the right ideology, then climate policies can be reversed, the “rule of law” can be respected, and Canada can return to the status quo of previous decades.

Longing for the past is generally considered a poor strategic response to structural change. The much better strategy for Canada is to proactively plan for the energy transition. And Alberta, as the epicentre of a Canadian hydrocarbon economy that still generates 11 per cent of the national GDP, should help lead the way forward. But Alberta also has to accept that the energy transition, with its emphasis on renewable electricity and the decline of fossil fuels, means that other provinces with different priorities and approaches will play bigger roles in determining national energy and climate policy.

Wrenching change is difficult, but the only antidote to fear and anger is hope and optimism.

Fortunately, there is much to be hopeful and optimistic about. Yes, there are risks to be mitigated because risk always accompanies change, but so does opportunity. As Canada stands on the cusp of transformational change in its energy system, economy, and society, does it have the courage to overcome populist resistance and act boldly before the opportunities pass us by?

Our country has proved to be intrepid in times of crisis, even visionary, and now is the time for more of that leadership.

The energy vision Canada needs

The energy transition cannot be stopped. The electrification of the future is inevitable. The pump that was primed in the second half of the 20th century now flows freely on its own and will soon be gushing.

“Decades of work went into technologies like solar and wind that hardly worked at all in the 1960s, gradually making them commercially viable,” says Chris Nelder, host of the popular The Energy Transition Show podcast. “Now they’re the cheapest resources around and they’re pushing fossil fuels off the grid. That principle holds true for many new energy technologies that are now market successes. Once you hit the tipping point, there’s really no way to put the genie back in the bottle.”

“Decades of work went into technologies like solar and wind that hardly worked at all in the 1960s, gradually making them commercially viable,” says Chris Nelder, host of the popular The Energy Transition Show podcast. “Now they’re the cheapest resources around and they’re pushing fossil fuels off the grid. That principle holds true for many new energy technologies that are now market successes. Once you hit the tipping point, there’s really no way to put the genie back in the bottle.”

This transformation is driven by what drives all major economic change – scientific research, new technologies, capital investment, changing consumer preferences, and, yes, public policy.

When it will end is the key question. That could happen as early as 2050 or the end of the century – or even well into the 22nd century. We don’t know because disruption on this scale and complexity is unprecedented. Nevertheless, the evidence is mounting that the transition is likely to be faster than slower.

This is why Western Canadian populism is not just wrong, but dangerous. To successfully adapt to major disruption, Canadians must be united on the strategy to move forward. They don’t have to agree on the details – Canada is too big and too diverse for unanimity – but if Canadians acknowledge the world is changing and agree that the country must change with it, the specifics can be worked out through vigorous public discussion.

That process is made far more difficult by noisy populists bent on resisting change to the bitter end. It is even more difficult because moderate Canadians don’t have a hopeful and optimistic alternate vision to rally around.

The Energi Declaration is meant to be that vision.

Is the energy transition progressing quickly or slowly?

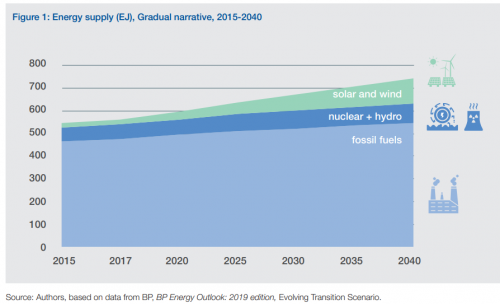

In a World Economic Forum white paper published in September, Kingsmill Bond and several prominent co-authors examined fast and gradual transition narratives. The Carbon Tracker financial analyst acknowledges the obvious, that the global energy system is enormously complex and accurate forecasting is impossible. Even developing plausible scenarios is difficult because sophisticated computer models have trouble keeping up with the pace of technology change.

“These organizations have failed to forecast the speed of growth of these new energy technologies for decades,” he told Energi Media. “For example, in the latest edition of the IEA’s World Energy Outlook, US solar is $95 per megawatt-hour, while the actual market price is below $50 and Lazard pegs it between $32 and $42.”

The gradual transition narrative is based on the “supertanker turning” metaphor: the global energy system is simply too big to change course on a dime. Inertia will dampen the forces of change. Advocates for the gradual point of view “extrapolate current patterns of policy, industry, consumption and investment, thus supporting planned carbon-intensive investment decisions,” according to the white paper.

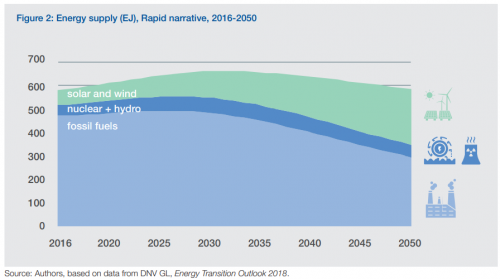

Allan Fogwill, economist and head of the Calgary-based Canadian Energy Research Institute, holds a gradual perspective. He thinks that in 2050 the energy landscape won’t look much different from today. Fossil fuels account for 80 per cent of current global primary energy and while renewables will chip away at that percentage, by mid-century it will still be well over half.

“We will likely see some change, but a transformation would require such a detailed adjustment outside of the normal course of economic growth and cultural development that I don’t see much of a change happening in the next 20 or 30 years,” he says.

The other side of the argument, the rapid transition narrative, agrees with Nelder that many new energy technologies are competitive now and that the 2020s will be a period of rapid adoption that will cause significant disruption to energy markets.

Think of the technology adoption curve as a hockey stick. Thousands of new energy innovations started at the toe of the blade and have been working their way to the heel. Now, many are ready to climb on to the shaft of the stick and begin the rapid ascent marked by an ever-increasing share of their respective markets.

The financial industry, concerned about climate risk and stranded hydrocarbon assets, is helping propel those technologies more quickly up the hockey stick shaft by shifting capital away from fossil fuels.

“The evidence on climate risk is compelling investors to reassess core assumptions about modern finance,” Blackrock Inc. Larry Fink, CEO of the firm with $7 trillion of assets under management, wrote corporate executives and clients in mid-January. “In the near future – and sooner than most anticipate – there will be a significant reallocation of capital.”

Accessibility and cost of capital are not the only risks facing hydrocarbon companies. Respected consultancies like Wood Mackenzie and giant oil companies like Suncor were predicting global peak oil demand between the mid-2030 and 2050, but pipeline company Kinder Morgan recently suggested it will arrive by 2030 and McKinsey’s technology case believes 2025 is possible.

Bond argues that the energy transition is ready for exponential growth and the oil and gas industry will be one of the first victims.

When battery prices were $195 per kilowatt (kwh) in 2017, leading American scientists and analysts were telling Energi Media that they expected $100 per kwh – generally considered to be the threshold when EVs achieve sticker price parity with ICE vehicles -within a decade.

That threshold appears to have been crossed by General Motors in just three years. In early March 2020 the American automaker introduced its new line of electric vehicles. Clever engineering lowered the use of cobalt by 70 per cent in completely re-designed batteries while raising range up to as high as 650 kilometres.

For the first time since the internal combustion engine was invented in the late 19th century, crude oil has a serious competitor. According to the Canadian Energy Regulator’s levelized cost of driving estimates, the existing generation of EVs already cost a penny or two less to drive per kilometre than gasoline-powered cars. The new generation of EVs – every automaker will be competing with GM – appear to be clearly less expensive to drive.

When low cost is combined with other benefits consumers value, like superior driving performance and low to zero emissions, the argument is strong for rapid adoption of EVs beginning during the early 2020s. The same case can be made for electric buses, which are being widely adopted in China – reportedly close to 400,000 already. Add electric work vehicles like delivery vans and millions of electric two-wheeled vehicles – very popular in Asia – and it becomes clear that the global electrification of transportation is well underway.

The case for the electrification of transportation – as well as buildings and industry – becomes even more compelling because of the rapid advances being made with renewable energy. Wind and solar plus storage electricity generation is now cheaper than new natural gas or coal power in many parts of the world. And the cost curves for renewable energy are still trending down.

There is one more important piece of the puzzle that supports exponential growth in energy technology adoption: enabling digital technologies like artificial intelligence and machine learning, automation, data collection and analytics, and many others. Digital tech is already helping make many technologies more efficient and lower-cost.

Even with these impressive advances, however, left to its own devices, the energy transition still might take the 50 to 100 years that energy transition expert Vaclav Smil suggests has been the norm for past transitions. The great unknown of this transition is the role governments may play thanks to international concern about global warming and climate change.

Climate Change: the energy transition’s accelerator pedal

That the House recognize that: (a) climate change is a real and urgent crisis, driven by human activity, that impacts the environment, biodiversity, Canadians’ health, and the Canadian economy…(d) action to support clean growth and meaningfully reduce greenhouse gas emissions in all parts of the economy are necessary…that the House declare that Canada is in a national climate emergency which requires, as a response, that Canada commit to meeting its national emissions target under the Paris Agreement… Liberal motion in the House of Commons, May 13, 2019.

This is the dominant climate change narrative in Canada: the planet is experiencing a climate crisis that requires humans to hold “global warming below two degrees Celsius and pursuing efforts to keep global warming below 1.5 degrees Celsius” by transitioning off fossil fuels as quickly as possible. From this point of view, climate change drives the energy transition.

What if we flipped that narrative on its head?

Now, the energy transition is driving change. We’ve already demonstrated that the transition “pump” was primed in the latter half of the 20th century, that the transition started around 2000, and that it is now self-sustaining.

The only real question to debate then is the pace of the transition. Will it arrive in 2050 or 2075 or 2100 or even later? The answer lies partly in how strongly world governments move on climate policy.

From this point of view, policy is the accelerator pedal of the energy transition. Push harder with higher carbon taxes, stricter regulations, and more subsidies for clean energy technology, and the transition speeds up.

Just how hard are Canadians willing to press the pedal?

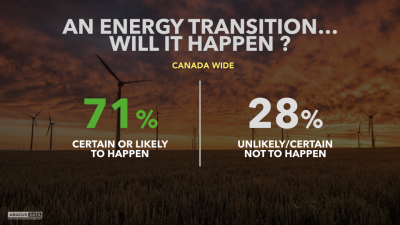

A January 2020 public opinion poll about Canada and the energy transition from Abacus Data is instructive. “A strong majority of Canadians believe the transition to energy that produces less impact on climate change is a global conversation, bound to happen, and something necessary whether we like it or not,” the pollster concluded. This view enjoyed strong support even in Alberta, where 68 per cent of those surveyed agreed that the “energy transition is certain or likely to happen,” compared to the national average of 73 per cent.

For the first time, climate change figured in the top three ballot issues during a federal election. Economists interviewed by Energi Media said that the Canadian government’s policies over the past decade were about three-quarters of what is required for Canada to meet its 2050 climate targets. During the campaign, the non-conservative parties pledged more and stronger policies that the economists think will bridge the gap and enable the country to achieve national net-zero emissions by 2050.

Canada’s commitment to net-zero emissions by 2050 based on energy transition worldview

In mid-2016, I interviewed then Natural Resources Minister Jim Carr about energy policy. When asked about the energy transition, the Winnipeg MP was animated as he explained that the transition was explicitly acknowledged by the Prime Minister and cabinet.

“[W]e must continue to generate wealth from our abundant natural resources to fund this transition to a low-carbon economy,” he said, echoing a now-standard talking point of the Canadian government.

Support for the energy transition and climate policy has spottier support among the provinces.

British Columbia adopted CleanBC, an aggressive plan to lower emissions from 64 Mt a year to 16 Mt a year by 2050, even with an expansion of natural gas production in the northeast and construction of the $40 billion LNG Canada liquefaction facility.

Former Alberta Premier Rachel Notley held roughly the same view of the energy transition as the federal Liberals, though she tended to see energy system change through the lens of social and climate policy, as well as the impact on working-class jobs. She also tended to the gradual change narrative.

“I don’t think anybody in cabinet or the premier thought that some dramatic transition was going to happen over the next 10 or even 20 years,” says Eric Denhoff, Notley’s deputy minister of environment and climate change. “But looking out 35 to 50 years the question was, what’s the role of oil and gas in the Alberta economy? It was intelligent to hedge our bets by supporting the growth of renewables.”

UCP leader Jason Kenney’s campaign energy narrative was about returning to energy policies that supported the growth of the hydrocarbon industry and the return of good-paying jobs. After forming government, Kenney changed the focus of Alberta’s energy and climate strategy, eliminating some policies (province-wide carbon tax, for example) and diluting others (the large emitter carbon tax), as he had promised during the election campaign.

The Premier, however, recently acknowledged that the global energy system is transforming.

During a panel discussion at Washington’s Wilson Center in early February, he discussed the energy transition. “I have a firm grasp of the obvious,” he later told the Calgary Herald in an interview. “There is no reasonable person that can deny that in the decades to come we will see a gradual shift from hydrocarbon-based energy to other forms of energy.”

Two weeks later, Teck Resources cancelled its $20 billion Frontier oil sands mine, citing climate policy concerns. The decision nicely demonstrates how the energy transition is affecting the hydrocarbon industry even as oil and gas consumption continues to rise.

Teck fiasco and Canadian climate policy

Teck’s February 23 withdrawal of the Frontier application may be viewed by historians as a turning point in the Canadian energy transition and climate policy debate.

“We support strong actions to enable the transition to a low carbon future. We are also strong supporters of Canada’s action on carbon pricing and other climate policies such as legislated caps for oil sands emissions,” Teck CEO Don Lindsay wrote in a letter to federal Environment and Climate Minister Jonathan Wilkenson.

He noted a major issue that deeply concerned his company, echoing asset management giant Blackrock Inc.’s mid-January letter to CEOs and investors warning of capital reallocation in the wake of climate change, investors demand climate policy certainty.

“[G]lobal capital markets are changing rapidly and investors and customers are increasingly looking for jurisdictions to have a framework in place that reconciles resource development and climate change, in order to produce the cleanest possible products,” he wrote. “This does not yet exist here today…”

Professor Harrie Vredenburg, Suncor Energy Chair, Haskayne School of Business at the University of Calgary, summed up the feelings of many in the Alberta oil and gas industry. “Premier Kenny’s political base is still arguing about whether climate change is real,” he told Energi Media. “We’re past that…world financial markets believe it’s real and that we need to do something about it. Now we can’t get investment dollars because of bickering between the governments.”

Professor Vredenburg’s stark assessment may not sound hopeful, but in truth conflict between provinces and Ottawa is hardly unusual during major policy shifts. In this case, the federal government is implementing climate policies consistent with the requirements of institutional investors like Blackrock and major resource companies like Teck.

Canadian climate policy

“Canada is on track to reduce our emissions by 30% by 2030, compared to 2005 levels…we committed to exceeding this target, and to joining countries around the world in reaching net-zero greenhouse gas emissions by 2050.” – Liberal leader Justin Trudeau during the 2019 election campaign.

Canadian governments have two overarching policy objectives: to decarbonize the existing energy system and to support the emergence of low or no-carbon energy technologies. Policymakers must also mitigate risks (the obvious example is Alberta and its carbon-intense oil sands) and help both the public and private sectors seize opportunities where they can be found (BC’s rapidly growing cleantech sector, for instance).

To achieve these objectives, governments have three types of climate policy levers they can pull: 1) carbon pricing (let the market decide how to lower emissions); 2) regulations (prescriptive requirements); 3) subsidies (encourage low-emission innovation and spur adoption of new technologies).

The federal parties are debating – and sometimes squabbling – about how hard to pull the various levers. Federal election results, however, sent a clear message to politicians: almost two-thirds of Canadians voted for parties with a strong climate plan.

The Liberals augmented their existing climate plan, the NDP proposed much more aggressive spending, and the Green Party promised to put Canada on a “war footing” to quickly decarbonize the economy. The much-criticized Conservative plan would have mostly done away with carbon pricing and regulations, relying far more on innovation subsidies that promised uncertain outcomes and timelines for results.

The Liberal minority government suggests Prime Minister Trudeau will be under pressure from the NDP and Greens to tread more heavily on the climate policy accelerator than he might otherwise.

Clean Canada, a report released in June by Environment and Climate Change Canada, lists 58 separate federal initiatives funded to the tune of $61 billion. Significant programs include the phase-out coal-fired power generation by 2030, introduction of the Clean Fuel Standard beginning in 2022, subsidies for EVs and financial support for the construction of over 1,000 EV charging stations, and regulations to reduce oil and gas production methane emissions by 45 per cent.

“The Liberals have laid out plans to build on the foundation of climate policies and programs they introduced while in government,” says Dan Woynillowicz, policy director at Clean Energy Canada. “Now they are signalling ambition to surpass our current 2030 target, as well as pledging to make Canada a net-zero emitter by 2050, consistent with both science and commitments from other leading countries.”

Canada has a history of setting greenhouse gas emissions targets and then not following through with the policy necessary to meet its commitments. The Liberal plan is a departure from the past, according to Pembina director of federal policy Isabelle Turcotte: “It’s a huge signal to Canadians in terms of saying we are serious about increasing our ambition and meeting those targets.”

Can Alberta and Saskatchewan remain misaligned with federal policy for long? Probably not.

Aboriginal title, indigenous law, and economic reconciliation

The question still to be answered is if Canada can boost its climate ambitions while continuing to approve natural resource development like oil, gas, and pipelines.

A significant speed bump for that strategy is aboriginal title, which in 2020 has been front and centre because of the Wetʼsuwetʼen First Nation blockade of the Coastal GasLink pipeline project and solidarity rail blockades by indigenous groups and environmental protesters across the country.

The issue at hand is the authority of the hereditary chiefs to invoke indigenous, pre-colonization law to forbid pipeline construction on Wetʼsuwetʼen traditional territories. The elected chief and council, who support Coastal GasLink, exercise authority under the Indian Act. Ideally, the hereditary chiefs and the elected leaders cooperate and work together harmoniously. In this case, that has proved difficult.

Why is this an issue of critical importance for the Canadian economy in general and the energy sector specifically? Most of British Columbia is unceded territory. While First Nations in other provinces signed treaties, those in BC did not. Landmark legal victories establishing aboriginal title have significant implications for Canadian resource development, chief among them oil and gas projects.

The 1997 Delgamuukw decision by the Supreme Court of Canada affirmed aboriginal title to traditional lands under Section 35 of the Constitution Act, 1982. The 2014 Tsilhqot’in decision conferred aboriginal title to1,700 square kilometres of land traditionally inhabited by the Tsilhqot’in for their exclusive use and management. These legal challenges were initiated by hereditary chiefs, not elected chiefs and councils.

While the Supreme Court imposed limitations on aboriginal title, First Nations across Canada have interpreted the rulings as conferring the right to withhold consent to resource development on their territories. After all, what are the constitutional rights to sovereignty and consultation if they don’t include the right to say “no”? On the other hand, recent Federal Court of Appeals’ judicial reviews of the Trans Mountain Expansion pipeline project specified that the right to consultation did not constitute a veto.

The unresolved issues of aboriginal sovereignty and title are further complicated by Canada’s commitment to reconciliation with indigenous peoples arising from the Truth and Reconciliation Commission and the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples. Resolving these issues is important to upholding the “honour of the Crown” – and, by extension, all Canadians – and creating the stability and certainty required by investors to fund natural resource projects.

British Columbia lawyer Robert Janes has proposed holding constitutional conferences – provisions for which are set out in Section 35 the Constitution Act – to work through aboriginal title. He points to countries like New Zealand and Nicaragua that created processes to recognize aboriginal title. A formal government-to-government approach would remove title disputes from the courts, which is currently the only venue to resolve them.

“I feel a bit sorry for the oil companies because we’re taking a huge societal problem – the relationship between indigenous people and Canada – and jamming it into the approval of a pipeline process,” he told Energi Media. “That’s because the governments of Canada and British Columbia and Alberta haven’t really bothered to take the time to figure out another process.”

The lesson of the Wetʼsuwetʼen hereditary chiefs opposition to Coastal GasLink, the Unis’tot’en camp, and solidarity rail blockades is that Canada must now take the time to figure out another process. And it must have an interim process that respects aboriginal rights and still permits resource development.

If Canada fails, it risks significant consequences, including missing an opportunity to advance reconciliation with indigenous peoples, as well as not fostering the investment environment needed for the hydrocarbon sector to adapt to the energy transition and for the clean energy economy to achieve its full potential.

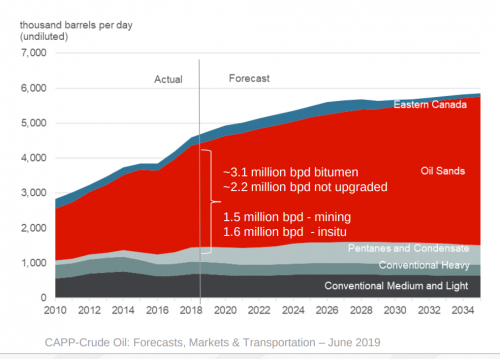

The hydrocarbon economy and the low-carbon pivot

Canada’s oil and gas sector is a huge contributor to the national economy. As of June 2019, Canada produces 4.687 million barrels per day (b/d) of crude oil, according to the Canadian Energy Regulator, three-quarters of it from the oil sands. Alberta is the largest producing province at 3.75 million b/d, followed by Saskatchewan at 470,000 b/d and Newfoundland and Labrador at 233,000 b/d. Alberta is also the largest natural gas producer at 10 billion bcfd, followed by BC at 5 bcfd and Saskatchewan at 400,000 cfd.

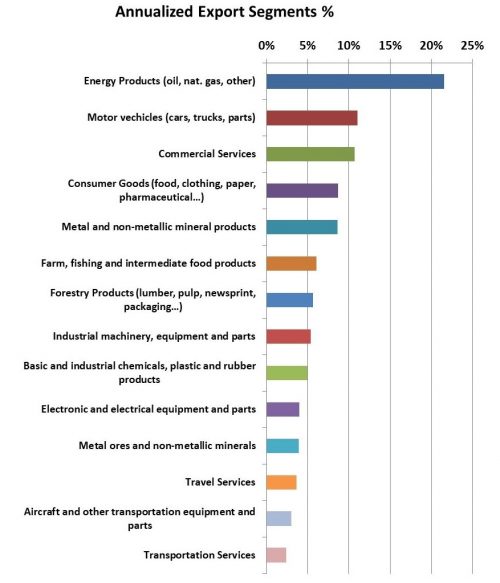

Canadian exports of mineral fuels, which include crude oil and natural gas, were valued at $98.4 billion in 2019 and accounted for 22 per cent of total exports, good for the top spot. Vehicles were a distant second at $61.4 billion and 13.8 per cent of national exports, followed by machinery at $34.8 billion (7.8%). The national hydrocarbon sector supports 180,00 direct jobs, down from 230,000 in 2014 (in Alberta, it is 136,000 jobs, down from 170,000).

Abandoning hydrocarbons would be economic suicide for Canada. Therefore, it’s in Canadians’ self-interest to ask if a long-term future for the hydrocarbon sector can be reconciled with a responsible approach to climate change that enables Canada to meet its Paris Agreement targets?

Energi Media is optimistic it can.

The strategy should have three phases: 1) aggressively decarbonize production from the existing oil and gas sector; 2) enable “cost and carbon-competitive” Canadian hydrocarbons to compete on international markets as long as possible by providing improved market access; 3) aggressively invest in hydrocarbon non-combustion applications, in particular building upon the impressive work already begun in Alberta on partial upgrading technology and “bitumen beyond combustion” research.

Decarbonizing crude oil production – the “best barrel”

“I think most would argue demand is increasing for a while and in that change, we want to be the barrel of oil that remains good for the planet,” says Arlene Strom, Suncor’s VP of sustainability and communications. “We want to harness technology and innovation to be part of a transformation to a low-carbon future.”

Oil sands producers MEG Energy, CNRL, and Cenovus have already declared aspirational goals of achieving net-zero emissions by 2050 and their competitors are likely to follow in the near future. Steam-assisted producers like Cenovus plan to replace natural gas-generated steam with solvents, mining companies are already using PFT (paraffinic froth treatment) to reduce emissions, while others are close to implementing innovations like CNRL’s IPEP, which processes bitumen ore at the mine face, reducing costs and emissions while eliminating tailings ponds.

Why can’t they do it faster, say by 2040 or 2030? Perhaps pressure from the public and governments could turn their aspirations into solid commitments and shorter timelines?

Still, the companies’ commitment to decarbonizing production is a good start and reason to be optimistic that they can be pressured or regulated into meeting more ambitious goals.

Decarbonizing natural gas production

Natural gas has slightly less than half (117 pounds of CO2 emitted per million British thermal units) the carbon intensity of coal (214.3 to 228.6 million pounds of CO2 per Btu). But it’s comprised of mostly methane (CH4), a potent greenhouse gas, that leaks from wells, pipelines and gathering systems, and facilities. If the leak rate is over 3 per cent, then that gas is considered to be more “dirty,” or carbon-intense, than coal.

A 2019 study from the Canadian Energy Research Institute (CERI) about methane emissions from the Canadian natural gas supply chain has some eye-popping conclusions.

Gas produced from the Montney formation in NE British Columbia has a leak rate of just 0.3 per cent. BC wells, pipelines and gathering systems, and facilities are newer, employ the latest technologies, and some of the latest projects are electrified using clean power from the BC Hydro grid. CERI estimates that the 5 billion cubic feet per day (bcfd) of BC gas generates 2.2 Mt of emissions annually.

Alberta gas is much dirtier: 10 bcfd generates 24.5 Mt. That is double the production, but roughly 11 times the emissions. The gas industry is older and leakier, and regulations aren’t as strict. CERI estimates that the leak rate is near or above 3 per cent on average and some fields are well above the threshold.

These conclusions are based upon existing data, which is notoriously unreliable. Until recently, measuring methane emission leaks was difficult, costly, and not frequent enough to generate adequate data. Researchers and industry, however, are moving in the right direction, spurred by new provincial regulations – backstopped by federal standards – designed to reduce emissions 40 to 45 per cent by 2025. Drones and satellite technologies, for instance, are being tested in the field and adoption is expected to spread quickly throughout the industry.

This is important because industry boosters claim that Canadian natural gas will make “green LNG” that can displace coal power generation in Asia. They point to the $40 billion LNG Canada facility that will be partially electrified when it’s completed in 2025 and funding from BC and Ottawa that will help further electrify production processes.

If LNG is made with NE BC or NW Alberta Montney gas, then based upon the available data, the “green LNG” claim has merit. If, however, West Coast LNG is made with dirty Alberta gas, then the claim is nothing more than greenwashing.

There would also be no guarantee Asian buyers of “green LNG” would use it to replace coal. Under the right circumstances, the LNG might even displace renewable power.

Canadians can be cautiously optimistic that LNG Canada will produce some of the lowest emission LNG in the world, but they should be skeptical about similar claims for Alberta gas and the assumption that “green LNG” would reduce coal consumption in countries like China and India.

LNG is not the only value-added application for natural gas.

Is hydrogen Canada’s low or no-carbon fuel of the future?

Canada is a leading provider of hydrogen – which is the simplest element: one proton, one electron – a carbonless energy carrier that can power locomotives, buses, heavy-duty trucks, and perhaps in the not too distant future, airplanes. Hydrogen can also be blended with natural gas for residential and commercial use.

Almost all of the current supply is manufactured from natural gas – is called “ Grey hydrogen” because the CO2 emissions generated during the process are currently released to the atmosphere We know how to change this Grey hydrogen into “Blue hydrogen” by injecting the resulting CO2 deep into porous rocks for permanent storage.

Electrolysis makes “Green hydrogen,” which has its place, but the production cost is currently three times that of Blue hydrogen. A nascent Green hydrogen industry has emerged in Quebec where cheap hydropower and free water are both plentiful.

Canada may have a competitive advantage in the emerging hydrogen economy.

Ballard Power Systems is one of the world’s leading manufacturers of automotive and industrial fuel cells for turning hydrogen into water and electricity. Carbon capture and sequestration technology costs are dropping rapidly and Alberta has the right geology and plenty of reservoirs to safely store the carbon dioxide. When electrolysis is cost-competitive, Canada’s largely clean electricity system can provide cheap wind and solar energy to power the process. There is even the possibility of making hydrogen on a small-scale for local and regional markets, creating new economic development opportunities in rural areas and the north.

The least expensive way to create hydrogen, however, is large-scale plants. In this case, hydrogen would be moved mostly by pipeline to supply other markets in Canada and could be shipped around the world, according to Calgary-based geologist Maggie Hanna. “Alberta is perfectly set up to make Blue hydrogen because of the tremendous amount of stranded, low-cost natural gas. We can use to make a high-value product,” she said. “And the porous rock of the Western Canadian Sedimentary Basin is perfect for safely sequestering carbon.”

She says preliminary numbers indicate that if producing provinces replaced the same amount of energy exported as oil and gas (at 2019 prices) with Blue hydrogen, Canada would make 1.5 to 2.5 times the revenue. She adds that perhaps a made-in-Alberta “hydrogen mission” – similar to the AOSTRA oils sands mission under Peter Lougheed – is in order at this time.

Hanna adds that the benefits of decarbonizing home heating, for example, justify investing in the industry now and eventually building hydrogen pipelines across Canada.

Getting crude oil to market: should pipelines be the last resort, not the first?

Canadians may be open to building new hydrogen-carrying pipelines, as Hannah suggests, but the same cannot be said about crude oil pipelines, especially those that transport diluted bitumen. Maybe it’s time for industry to devise a new strategy to get oil to market.

Industry thinks about “market access” the same way it did in the 1950s when the original Trans Mountain was built: if it’s profitable it should be built, that economic benefits trump aboriginal title, environmental concerns, and local opposition. Pipeline entitlement is engrained in oil patch culture.

In fairness to pipeline companies, however, they have been following the rules laid out by governments. Furthermore, technology is vastly improved, materials and construction methods are better, integrity and safety management is an important part of corporate culture, and environmental assessments of their projects are more rigorous than never. Consequently, while spills garner more media attention, the data shows that the number of spills and the volumes released are significantly lower than a decade ago.

As pipeline advocates frequently point out, pipelines are demonstrably the safest and cheapest way to transport crude oil. But, given opposition to new pipelines and rapidly evolving oil markets, are they the best option for shipping oil in the future?

According to the CER’s 2019 Energy Future report, Canada has the time to think carefully about market access: “If announced pipeline projects proceed as planned, along with continued volumes of crude by rail, there would be adequate takeaway capacity to accommodate production growth over the next 20 years.” Crude oil supply is forecast to increase by 50 per cent from just over 4 million b/d now to over 6 million b/d over the next two decades.

If the CER scenario is at all plausible, Canada needs to do the hard work to fix the market access problem. The first step would be to acknowledge that building pipelines in the modern era is very difficult in most of North America.

University of Houston energy law professor Victor Flatt told Energi Media that any time an American oil or gas pipeline project crosses a state border, it is vigorously opposed and litigated. The average length of the review is eight years, not much different than Canada. To make matters even more complex, banks like HSBC and re-insurers like the Zurich Group will no longer finance pipelines carrying bitumen.

Local opposition and environmental groups – fierce pipeline opponents in both countries – are not going away. First Nations’ assertion of aboriginal title adds another significant layer of complexity in Canada. That resistance can’t be suppressed by stiff penalties and jail terms, nor should it be, since lawful protest is a constitutionally protected right of all Canadians.

Perhaps the better way to approach market access is to consider crude oil pipelines the last resort instead of the first. Fortunately for the oil sands, innovation has provided three new technologies for shipping bitumen that are either about to be commercialized or they’re very close to it.

In late February, the Alberta government approved the construction of a 50,000 b/d diluent recovery unit near Hardisty. Almost all of the diluent will be stripped from diluted bitumen (dilbit), leaving “DRUbit,” bitumen that can be shipped by rail. Proponents, Calgary-based Gibson Energy and US Development Group, claim that saving the diluent (currently imported from Chicago) for re-use in oil sands production and stuffing more bitumen in a rail car, makes DRUbit competitive with pipeline tolls.

Another innovation that enables shipping bitumen without building new pipelines is partial upgrading. Bitumen, which is the consistency of peanut butter, is upgraded to a heavy or medium crude oil that flows in a pipeline without the addition of diluent. Partial upgrading can add $10 to $15 per barrel of value, lower emissions at the refinery, and free up hundreds of thousands of barrels of space in existing pipelines. The first commercial partial upgrading facility will be Fractal Systems’ EJS Regional Hub with a processing capacity of up to 70,000 b/d of dilbit (50,000 b/d of bitumen). Cenovus Energy will be the first customer, providing 20,000 b/d to 35,000 b/d of dilbit.

Partial upgrading is an Alberta-developed technology that could give Canada a huge competitive advantage over heavy crude oil suppliers like Venezuela, Mexico, and Brazil. The Notley government committed $2.1 billion to help companies take their technologies to the commercial stage. Unfortunately, the Kenney government cancelled the program, citing “higher financial risk to government.”

The final new approach is Canapux, solid dry pellets of bitumen that can be shipped by rail. They float in water and do not leak or dissolve, significantly lowering risk of environmental contamination to oceans, lakes and rivers in the event of a spill. CN Rail is spearheading the project, partnering with the Heart Lake First Nation on a $50 million plant in Lac La Biche County in northeastern Alberta, south of Fort McMurray. It will process up to 10,000 barrels of bitumen and about 275 tonnes of plastic per day, with construction starting in 2020.

Both DRUbit and Canapux are shipped by rail, which has a number of advantages over pipelines. Producers prize “optionality,” the flexibility to send their oil to other markets where prices are higher, which is not possible with pipelines. When shipping by rail, crude is considered a hazardous good, covered by existing regulations, and no lengthy environmental assessment is required. Adding new capacity is a matter of months, not a decade or more from conception to final in-service date; we should acknowledge that shipping more bitumen by rail will strain the national railway system and solutions will need to be found. Finally, pipelines will be in service for decades, raising the risk of them becoming stranded assets as oil demand eventually declines.

Can a combination of DRUbit, partial upgrading, and Canapux replace the need for new pipelines? Canada has a decade to find out. Canadians should be optimistic that innovation has produced three alternatives to shipping oil by pipeline.

If by 2030 the three technologies have not proved out and there is still a market for heavy crude oil, then if Canada has to build a pipeline, let First Nations own and lead the project. A coalition of Nations and indigneous communities is already trying to buy a majority of the government-owned corporation that owns Trans Mountain and Kinder Morgan Canada’s former assets.

“Business is the equalizer,” JP Gladu, CEO of the Canadian Council for Aboriginal Business, told Energi Media. “When you have business agreements – either equity, procurement, or benefit agreements, – a lot of the other consultation stuff starts to fall in place.”

Suggesting that non-pipeline options for shipping crude oil should come before new pipelines, and that if a pipeline has to be built it should be majority-owned by First Nations, will probably not be warmly received by the industry establishment. That same establishment, however, has had more than a decade to come up with solutions to the market access issue. Thus far, it has failed spectacularly.

Beyond Combustion – bitumen, natural gas

Peak oil demand is a decade, perhaps two, away. The future of crude oil as a feedstock for transportation fuels looks uncertain after 2040. Fortunately for Canada, considerable research has begun into non-combustion uses for oil and gas, particularly bitumen.

Ironically, bitumen’s high carbon-content makes it an excellent feedstock for materials like carbon-fibre, according to Bryan Helfenbaum, executive director of advanced hydrocarbons and clean resources for Alberta Innovates, a research and innovation agency of the provincial government. He heads up research into how bitumen can be used to make carbon fibre (thin strands of carbon woven together, very strong), asphaltenes (paving material for roads, asphalt shingles), and polymers (synthetic rubber, silicone).

“Just the carbon fibre opportunity alone would quintuple the value of a barrel [of bitumen],” says Helfenbaum. “Depending on how much of the value chain we capture, we could be pumping out $50 to $100 hundred billion dollars a year in revenue. So it’s a massive opportunity. It really is transformative.”

Commercialization of carbon fibre products could occur as early as five to seven years from now, though it will probably take longer. Finding qualified and experienced technical workers, not funding, is the big challenge.

A big advantage for the Bitumen Beyond Combustion program is that some of the oil sands companies – with deep pockets and plenty of technical expertise – have been at the table since it started. These giant corporations may not want to diversify into carbon fibre manufacturing, but many of them are already integrated with upgraders and refineries, so adding value to their raw feedstock isn’t foreign, either.

Canadians should be very optimistic that one of the country’s biggest industries is actively investigating new technologies, products, and markets as the global energy system continues to pivot to a low-carbon future.

A 50-year strategy for Canadian hydrocarbons

If we view the energy transition as the bus and climate policy as the accelerator pedal, then how should we view the long-term prospects for Canada’s hydrocarbon sector?

If global governments have a light foot on the policy pedal and the energy transition is gradual and not fast, then the need for a post-combustion strategy could be viewed as less urgent.

But what if pressure on the policy pedal becomes increasingly strong as nations grapple with ever more severe climate-related disasters? What if governments decide a lead foot on the pedal is necessary?

But what if pressure on the policy pedal becomes increasingly strong as nations grapple with ever more severe climate-related disasters? What if governments decide a lead foot on the pedal is necessary?

Would it not be prudent for Canada to hope for the best, but plan for the worst? What might that strategy look like?

The oil sands producers are hard at work on the first step, decarbonizing production. And it appears the market access conundrum may have a solution in the form of DRUbit, partial upgrading, and Canapux that doesn’t require more pipelines. The third part of the strategy, non-combustion applications for bitumen, is now underway.

One can imagine an energy future sometime after 2050 where heavy crude oil demand for fuel has shrunk to the point where Canadian producers are losing market and the end is in sight. If Bitumen Beyond Combustion has developed as hoped, they would long ago have been diverting more and more of their bitumen supply to Canadian processors.

In a perfect world, the companies make a seamless transition from combustion to non-combustion markets, thus ensuring the sector a longer life – perhaps well beyond 2100 – than many today think is possible.

If there is no demand for bitumen to be refined into fuel, or the companies cannot transition to the cost and carbon-competitive “best barrel,” then the oil sands will be a sunset industry and markets will determine its fate.

But the existence of a potential path to the long-term preservation of a vital sector of the Canadian economy is certainly grounds for hope and optimism.

Canadian energy politics and narratives

When it comes to energy issues, narrative matters. How Canadians think and talk about energy determines in part the policy choices available to governments, as well as the business and investment environment we hope will attract capital and expertise. Currently, the national discourse about energy is dominated by two polarizing narratives, “leave it in the ground” and “drill, baby, drill.” Both camps represent a small minority of Canadians.

When it comes to energy issues, narrative matters. How Canadians think and talk about energy determines in part the policy choices available to governments, as well as the business and investment environment we hope will attract capital and expertise. Currently, the national discourse about energy is dominated by two polarizing narratives, “leave it in the ground” and “drill, baby, drill.” Both camps represent a small minority of Canadians.

Public opinion polling data is very clear that a large majority – probably between 60% and 70% – of Canadians support the energy transition and expect their governments to enact policies that encourage the adoption of clean energy technologies. In return, voters will support more oil and gas development as long as emissions are falling and markets exist for hydrocarbons.

Think of it as the national energy pact. Converting the Canadian energy pact into a vision for the future, however, is easier said than done. Let’s start by acknowledging that both of the extreme camps make some valid arguments.

The “leave it in the ground” proponents are quite right that global warming is an existential threat to humanity and that transitioning off fossil fuels must happen if the temperature rise is to be kept between 1.5C and 2C. Business as usual is not an option, the hydrocarbon industry should not be permitted to greenwash its record, and change cannot proceed at a slower pace simply because it’s optimal for engineers and provides the best returns for investors.

“Drill, baby, drill” boosters are right that global oil and gas demand will likely rise for a time before plateauing and if the industry can decarbonize the production of hydrocarbons while addressing some outstanding issues (oil sands tailings ponds and GHG emissions are two big ones), then Canadian producers should be allowed to compete against countries that aren’t decarbonizing or fixing environmental problems. Progressive CEOs understand that carbon-competitiveness and high environmental standards will be the table stakes in tomorrow’s oil and gas markets.

Ideally, the clash of these two worldviews over time would lead to a middle-ground accommodation, a compromise capable of advancing the interests of each camp while achieving the larger objectives of adapting to the energy transition and meeting Canada’s Paris Agreement targets. Unfortunately, the necessary compromise has never been reached. The middle ground is still a no-man’s land of bitter trench warfare with neither side giving an inch.

The time has come to end the war and negotiate the energy peace Canada needs.

The time is ripe for moderate leaders to step up with a more forward-looking vision for national energy development, one that leads the country toward an optimistic energy future more aligned with the energy transition and global efforts to fight climate change.

The Energi Declaration was written to offer guidance to those leaders.

COVID-19 postscript

The Energi Declaration was mostly written before the coronavirus pandemic arrived in Canada. From the perspective of late March, 2020 it is still far too early to guess what the post-pandemic energy landscape will look like. But a quiet idea has crept into the public discourse: that when the worst of the health threat is over, maybe humanity will now be ready to significantly speed up the energy transition using climate policies.

Maybe the energy status quo is finished.

As a significant energy-producing nation, Canada should at the very least contemplate this scenario. If Canadians are willing to have that discussion, it is our hope that the Energi Declaration may make a constructive contribution to the conversation.

Signed

Markham Hislop

Energy journalist/publisher

Energi Media